It’s easy to forget amidst the concern over sprawl that agriculture is still the dominant human impact on the land. Perhaps that’s because it’s easy to rationalize the consequences of agriculture’s land use—it feeds us, after all. But that shouldn’t dissuade us from finding ways to improve farm efficiency. Global population growth shows no signs of stopping before 2050, and rising standards of living mean everyone will be consuming more calories than ever. And why shouldn’t many of them? Malnutrition still plagues much of the developing world.

That’s not to say we haven’t made progress. The Green Revolution boosted crop production by between 250 and 300 percent while only using about 12 percent more acreage. This put a serious dent in starvation rates, but it hasn’t been enough to eradicate the problem nor will it be enough to keep it at bay in the future. Troublingly, crop yields have begun to level off, raising concerns that the the only way to meet the inexorably rising demand will be to put more land under cultivation.

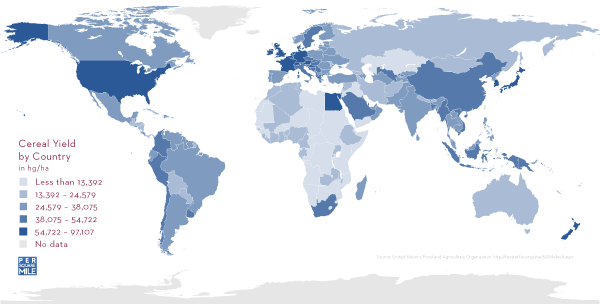

As a humanitarian and conservationist, both prospects alarm me. I’m not alone. Jason Clay, a vice president at the World Wildlife Fund, published an essay in the latest issue of Nature raising many of the same concerns. He offers eight strategies to alleviate the problem, all of which are forward thinking but only some of which will be easy to implement. Clay also focuses intensely on how these strategies can help Africa, a continent in dire need of more productive agriculture, as you can see in a worldwide map of crop yields (cereal yields are mapped below). He also rightly points out that those strategies need to be implemented in the developed world. But Clay fails to say how doing so will benefit nations developed and developing. That’s where I’d like to step in.

view larger

view interactive version

Clay’s eight strategies run the gamut. The careful study of genomes can lead to greatly improved yields. But his approach is different in a subtle yet important way from many genetically modified crops. Rather than inserting genes from other organisms, he proposes geneticists speed the old process of selective breeding, where the best traits are kept and the rest discarded. He also supports training farmers in best practices, rehabilitating degraded land, reducing waste from field to table, raising the efficiency of inputs like fertilizer and irrigation, improving soil organic matter, and the reducing consumption in developed nations (which would have obvious benefits for their citizens). Clay also says giving farmers title to their land—something often absent in developing nations—would raise yields by encouraging stewardship.

Poor practices and low yields can lead to a cycle of cultivation and abandonment, which I think is part of the concern in Africa. Unless broken, some of the world’s most important ecosystems will be destroyed. Developed nations have been pushing conservation in developing nations, hoping they won’t repeat the mistakes many of us made decades or centuries ago. However, many people in developing nations have more urgent concerns, like food. Here’s where improvements in the developed world could help. Further raising crop yields in developed nations would not only allow us to save more of our land for conservation—increasing total protected area worldwide—we could direct the surpluses toward a food-for-conservation effort, similar to those proposed for carbon offsets. Such programs would require careful implementation to encourage self-sufficiency and prevent developed nations from lording over the poor.

Developed nations should also look inwards to expand their crop production before going abroad. That’s not to say developing nations should abandon the export market. Crop exports do provide poor nations with cash. But there is a growing trend of foreign interests purchasing cropland and exporting the harvests, removing local farmers and reducing the value of exports to the local economy. For example, China, India, and other countries have purchased or are leasing large tracts of land in Africa for that purpose. While there are good arguments for the globalization of the food supply—increased efficiency can offset the need for new tillage—it shouldn’t be done at the expense of local farmers or virgin land.

In essence, Europe, China, North America, and other developed regions need to further raise their agricultural efficiency and lend a hand to those who are struggling to do so. That can include food aid, but should also include training, research into more sustainable agricultural techniques, and further technology transfers. Many of these already take place, but need to be more creative and larger in scale.

Implementing the same strategies in developed nations that Clay suggests for the developing world would be sensible international policy. Rather than exhorting developing nations to “make better choices” and not repeat the mistakes we made in the past, we should be putting these strategies into action ourselves. It would help fight the appearance of imperialism and perhaps lead to more trusting international relationships, sending the signal that we’re all in this together.

Sources:

Clay, J. (2011). Freeze the footprint of food Nature, 475 (7356), 287-289 DOI: 10.1038/475287a

Foley, J. et al. (2005). Global Consequences of Land Use Science, 309 (5734), 570-574 DOI: 10.1126/science.1111772

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 2011. FAOSTAT 2009 Crop Data. (available online)

Photo by five blondes.

Related posts: