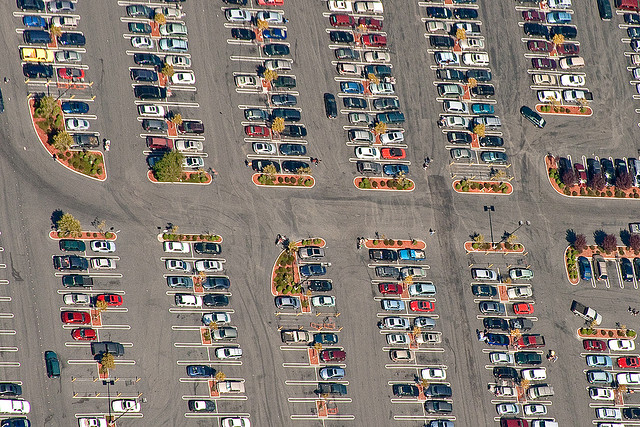

It’s sad but true. Americans likely have 800 million parking spaces at their disposal and many of us (myself included) have driven round and round the block looking for a spot. What gives? It’s the distribution, of course. Parking availability is heavily skewed to the places that seem to need it the least, like the suburbs. If you’re in a big city, that knowledge is a maddening fact of life. But there’s more to our surfeit of spots than simple frustration. Parking represents a large and often hidden cost of driving, and according to a study that estimated the number of spots, it adds to cars’ already substantial carbon footprints.

A team of engineers from UC Berkeley assembled a virtual dossier of parking spaces across the country. They drew on data from commercial parking companies, policy reports, government databases, surveys, and the urban planner’s old rule-of-thumb—eight parking spaces per car. The authors estimate the number of spots ranges from a low of 105 million (just those reported by an industry group) to a high of 2 billion (the rule-of-thumb estimate). The middle three estimates each fell around 800 million spaces, the number on which most media reports seem to have settled as the correct guess.¹

It’s likely then that the U.S. has over 500 million more parking spaces than registered vehicles. For every 100 square meters of roadway, there is about 50 square meters of parking space. In sum, the amount of land devoted roadways and parking in the U.S. can cover the entire state of West Virginia—that’s about 24,000 square miles or 62,000 square kilometers. If we use the study’s middle of the road estimates, a third of that number—about the size of New Jersey—is solely devoted to parking. Clearly, we have too much parking space in this country. The glut of free and cheap parking artificially lowers the cost of driving, encouraging people to stay in their cars, planners to pave more land, and politicians to look unfavorably on mass transit.

Even in dense urban areas, parking is woefully underpriced, according to Donald Shoup, the “prophet of parking.” Fortunately, many cities are starting to ratchet up prices. San Francisco has even gone so far as to pilot smart meters that adjust rates based on the availability of spaces as measured by in-road wireless sensors. The goal is to leave 15 percent of spaces free at all times, a number Shoup’s research says minimizes the amount of time people hunt for parking spaces and thus reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

Smarter use of parking spaces is not the only way to limit their environmental impact. Reducing the number would also create some some drastic results. The energy and resources that go into paving for parking increases carbon emissions by 62 percent for sedans and SUVs and 67 percent for pickup trucks. Plus, associated emissions of soot and volatile organic compounds are also substantially higher, offsetting some of the benefits of catalytic converters on cars and trucks. Less land paved by asphalt would also reduce the urban heat island effect, which in turn would lessen the strain on buildings’ air conditioning systems.

The inventory’s cataloged environmental impacts, though extensive, are only part of the story. For example, the study does not calculate the additional amount of roadway and other infrastructure that is required to accommodate massive parking lots and wider streets. Many communities require wide roadways for street parking despite the fact that nearly all of their houses and apartment buildings have off-street parking. The reduction in paved areas would be substantial if these communities would build narrower roads and restrict parking to one side. City footprints would also shrink. Even in existing neighborhoods, road rebuilding projects could pare down street widths and widen parkways.² Though the amount of added greenery would seem small, a 30 percent reduction in impervious roadway surfaces would ease the strain on sewer and water treatment systems and help mitigate flooding.

To think, our cities could be radically different if we’d just reconsider the number of parking spaces we really need.

- Many articles on the study report the authors claim 800 million is the most likely estimate, but I couldn’t find confirmation of that anywhere in the article. Still, 2 billion seems unreasonably high, and 105 million improbably low, so 800 million is a good guess. ↩

- Also known as tree lawns, sidewalk buffers, devil strips, city grass, and so on. If you need a picture, here you go. ↩

Source:

Chester, M., Horvath, A., & Madanat, S. (2010). Parking infrastructure: energy, emissions, and automobile life-cycle environmental accounting Environmental Research Letters, 5 (3) DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/5/3/034001

Photo by Troy Holden.