Planners looking to imbue their development with a little old school appeal have a best friend in alleys. The petite thoroughfares tuck bland garage doors behind friendlier looking houses, shrink lots to squeeze in more housing, and leave sidewalks and streets that are free of driveways and curb cuts. Alleys have their charm, I admit. They harken back to the day when they hosted neighborhood stickball games or were the best place to ride a bike. New Urbanists—planners, architects, and developers who seek to recreate Small Town, U.S.A.—have latched on to alleys. They claim that the narrow passages leave a streetscape that’s friendlier to pedestrians. It’s a good argument, but I think New Urbanists just have a bad case of nostalgia.

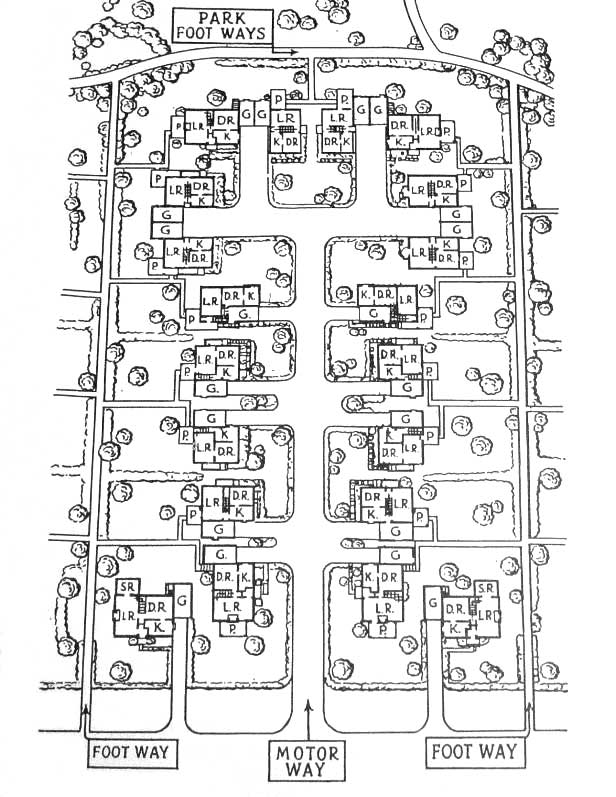

Here’s why: If pedestrian friendliness and walkable neighborhoods are really what New Urbanist planners seek, then they would do away with the alley entirely. Well, not entirely. Rather, they would pick up a neighborhood’s roads and plop them down in place of the alleys. In the street’s place would be narrower pedestrian and bike paths. The roadway would remain behind the houses, functioning as an alley in spirit while feeding roads that carry traffic to larger arterials. People and cars could both travel in relative peace.

The separation of foot and vehicle traffic sounds like a brilliant idea, one that could bequeath neighborhoods with New Urbanist density and pedestrian friendliness while preserving a bit more space for yards and gardens. In fact, I think it’s so brilliant that I wish I could claim it as my own. Alas, I cannot. Credit goes to Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, and Marjorie Sewell Cautley, the planners of Radburn, New Jersey.

Radburn was cooked up in the 1920s. At the time, the success of the automobile encouraged experimentation with city plans. The Radburn plan was at the cutting edge. Cars brought a new freedom of movement that many planners translated into larger lots and sweeping lanes that evoked the countryside, à la Frank Lloyd Wright’s proposed Broadacre City. But Stein, Wright, and Cautley took things in a slightly different direction, shrinking roads and lots back to more manageable sizes.

Radburn was cooked up in the 1920s. At the time, the success of the automobile encouraged experimentation with city plans. The Radburn plan was at the cutting edge. Cars brought a new freedom of movement that many planners translated into larger lots and sweeping lanes that evoked the countryside, à la Frank Lloyd Wright’s proposed Broadacre City. But Stein, Wright, and Cautley took things in a slightly different direction, shrinking roads and lots back to more manageable sizes.

I first read about Stein, Wright, and Cautley’s plans for Radburn in The American City: What Works, What Doesn’t. It was the plan’s walkways that captured my imagination. They weren’t just footpaths—they were spiritual successor to the road. Front doors opened on to the paths. Pedestrians never had to worry about vehicular traffic. Instead, the footways passed under streets, keeping dangerous automobiles separate from pedestrians—especially children walking to school.¹ Since I read about Radburn, I’ve been so taken by the idea of “roadless” neighborhoods that they’ve backdropped my dreams. I kid you not. I often walk through Radburnesque towns in my sleep-induced hallucinations.

Alas, Radburn was never finished. Its pioneering planners and their model city ran smack into the financial realities of the Great Depression. Only one of the pedestrian underpasses—what was to be one of Radburn’s signature elements—was built. Instead, Radburn is best known for introducing the 20th century to the cul-de-sac and the superblock, a collection of streets bounded by four major arterial roads. Alexander Garvin, author of The American City, says these two planning concepts were “so much more important” than the footpaths and their underpasses. He was certainly right about their role in the last century, but I’d like to think the next hundred years will prove him wrong.

- An interesting side note: Radburn’s planners defined each neighborhoods by the “population for which one elementary school is ordinarily required”. ↩

Source:

Alexander Garvin (2002). Residential Suburbs The American City: What Works, What Doesn’t, 305-343 ISBN: 0071373675

Photo by themikebot.

Related post: