This post originally appeared on Scientific American’s Guest Blog.

High density living seems like a particularly modern phenomenon. After all, the first subway didn’t run until 1863 and the first skyscraper wasn’t built until 1885. While cities have existed for thousands of years—some with population densities that rival today’s major metropolises—most of humanity has lived at relatively low densities until recently, close to the land and the resources it provided. Before farming, nearly everyone was directly involved in the day-to-day hunting and gathering of food, which required living at even lower densities. It would seem as though our current proclivity for high density living runs counter to our biological underpinnings, that density has been thrust upon us by the demands of modern life.

![]() It’s easy to arrive at that conclusion, in part because density is a hot topic these days. More than 50 percent of the world’s population now lives in cities—a fact repeated so often it’s almost a litany. But reciting that phrase doesn’t reveal the subtle effects implied by the drastic demographic shift. People migrating from the countryside face untold challenges wrought by density. Cities are complex places, fraught with crime, diseases, and pollution. Yet cities are also places of great dynamism, creativity, and productivity. Clearly, the benefits outweigh the drawbacks or else cities would have dissolved back into the landscape.

It’s easy to arrive at that conclusion, in part because density is a hot topic these days. More than 50 percent of the world’s population now lives in cities—a fact repeated so often it’s almost a litany. But reciting that phrase doesn’t reveal the subtle effects implied by the drastic demographic shift. People migrating from the countryside face untold challenges wrought by density. Cities are complex places, fraught with crime, diseases, and pollution. Yet cities are also places of great dynamism, creativity, and productivity. Clearly, the benefits outweigh the drawbacks or else cities would have dissolved back into the landscape.

The benefits of living close to other people are evident even to hunter-gatherers. Though their societies have changed over the millennia, studying characteristics of present-day hunter-gatherers can let us peer into the past. That’s what was done by three anthropologists—Marcus Hamilton, Bruce Milne, and Robert Walker—and one ecologist—Jim Brown. In the process, they seem to have discovered a fundamental law that drives human agglomeration. Though their survey of 339 present-day hunter-gatherer societies doesn’t explicitly mention cities, it does show that as populations grow, people tend to live closer together—much closer together. For every doubling of population, the home ranges of hunter-gatherer groups increased by only 70 percent.

The way home ranges scale with population follows a mathematical relationship known as a power law. Graphs of power laws bend like a graceful limbo dancer—sharply at the base and more gradually thereafter—toward one axis or another, depending on the nature of the relationship. They only straighten when plotted against logarithmic axes—the kind that step from 1 to 10 to 100 and so on. One variable, known as the scaling exponent, is responsible for these attributes.

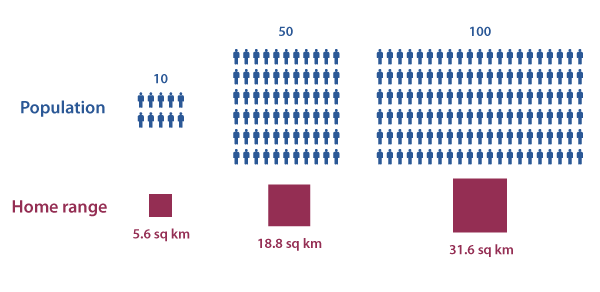

Fig. 1 Hunter-gatherer home ranges scale to the three-fourths power. Above are representations of three populations and the size of their home range according to this relationship.

To see how scaling exponents apply in the case of hunter-gatherer territories, let’s look at the range of possible values and what each would mean in terms of density. If the exponent were equal to one, then home ranges would scale linearly with population size—10 people would occupy 10 square miles and 100 people would occupy 100 square miles. If the exponent were 1.2, then a group of 100 would occupy 250 square miles. And if the exponent were 0.75, a group of 100 people will only occupy 32 square miles. This last one is what Hamilton and his co-authors found.

Their result is the average of 339 societies, and there’s a bit of heterogeneity within that statistic. Not every group has a perfectly “average” way of hunting and gathering. Some hunt more, some gather more. Some find food on land, others in the water. Where and how hunter-gatherers get their food has a large impact on how densely they live, causing the density exponent to deviate slightly or greatly from three-quarters. For instance, groups which derive more than 40 percent of their food from hunting require larger territories because prey is not always evenly distributed or easily found. Their home ranges scale to the nine-tenths power, indicating sparser living. Gatherers require less space—their home ranges’ scale at the 0.64 power—largely due to plants’ sedentary lifestyles.

Hunter-gatherer societies which draw food from the water lived more compactly, too. The home range of aquatic foragers was consistently smaller across the range of population sizes—their exponent was 0.78 versus terrestrial foragers’ 0.79. Hamilton and his colleagues suspect this is because food from rivers, lakes, and ocean shores is more abundant and predictable than comparable terrestrial ecosystems.

But no matter what types of food are consumed, the overall trend remains the same. Every additional person requires less land than the previous one. That’s an important statement. Not only does it say we’re hardwired for density, it also says a group becomes 15 percent more efficient at extracting resources from the land every time their population doubles. Each successive doubling in turn frees up 15 percent more resources to be directed towards something other than hunting and gathering. In other words, complex societies didn’t just evolve as a way to cope with high-density—they evolved in part because of high density.

Update: The figure in this post originally reported 10.8 sq km for a group of 50 people. It should have been 18.8 sq km. The figure has been updated.

Source:

Hamilton, M., Milne, B., Walker, R., & Brown, J. (2007). Nonlinear scaling of space use in human hunter-gatherers Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104 (11), 4765-4769 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0611197104

Photo by Gruban.

Related posts:

The curious relationship between place names and population density

Density in the pre-Columbian United States: A look at Cahokia