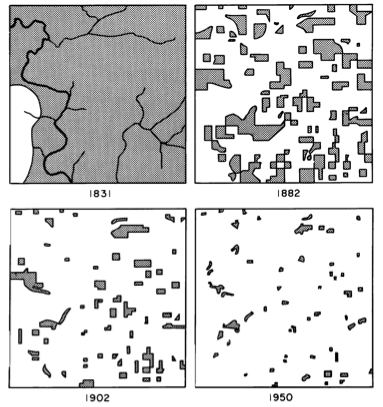

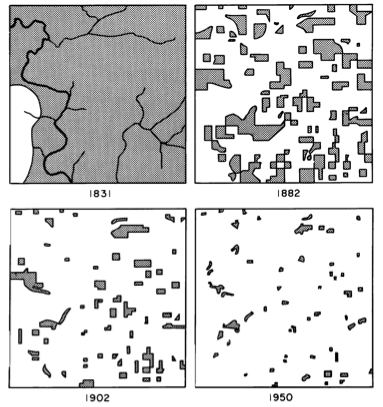

John T. Curtis, a 20th century ecologist, drafted a simple, four-panel map that appeared in a volume of research presciently titled Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth. It’s an important map for a number of reasons, not least of which was the impact it had on my life. This is how I described it in my first non-introductory post here at Per Square Mile:

It is a simple map, or rather series of maps. Four panels, four dates—from left to right: 1831, 1882, 1902, and 1950. In each successive panel, the dark swaths of ink that represented forest cover in Cadiz Township, Wisconsin, grew successively smaller and more fragmented.

It’s a powerful image, one that drives home just how much we have affected this world. But like many images, there’s a lot that’s both implied and unknown. One of the unknowns of Curtis’s map was how life was faring in those small flecks floating in a sea of farm fields.

Now, we may be a step closer to understanding how dire that situation really is. A team lead by David Bickford, a professor at the National University of Singapore, recently wrapped up a 25-year study of forest patches turned into islands by the filling of the Chiew Larn Reservoir in Thailand in 1986 and 1987. The reservoir flooded nearly 64 square miles (165 square kilometers), isolating more than 100 patches of species-rich tropical forest. What had been hilltops were transformed into islands. Five to seven years after the flooding, the research team surveyed small mammal populations on 12 of the islands and 16 of the islands 25 to 26 years after.¹ None of the islands had signs of human impact.

Bickford and his team discovered that species vanished from the islands at an astonishing rate. Nearly all of the native small mammals were gone on the smaller islands (under 24 acres or 10 ha) in just five years, while on larger islands (24-138 acres or 10-56 ha), they were nearly extinct after 25 years. Their findings jibes with a message conservation biologists have been sharing for some time—the smaller the island, the fewer the species, and the longer the time since isolation from the mainland, the fewer species.

There are a number of possible reasons why small mammals disappeared from these islands, none of which are very heartening. The researchers point out that invasive Malaysian field rats were a problem on the islands, likely outcompeting or outright killing the native species. By the 25-year time point, “all islands were dominated by the invasive rodent and if not already in ecological meltdown, were well on their way to becoming Rattus monocultures,” Bickford and his team note.

But there are other possible reasons, too. Small habitat patches may not be large enough to sustain a viable population. When ranges are compressed, populations face a number of hardships, from increased competition for resources to inbreeding and intrapopulation strife that can raise stress, increase conflict, and lower breeding rates.

This study isn’t just about isolated islands in a remote corner of Thailand. It’s also about the flecks of land we cordon off every time we fell a forest, plow a field, or plat a subdivision. We’re creating small islands of habitat surrounded by seas of human dominance. Certainly some animals and plants can move between those islands, but not all do and not all at rates needed to sustain remnant populations. Some animals may be better than others at navigating human oceans, but even they may be doomed, unable to withstand competition or predation from introduced species. If we are to minimizing the impact we have on the environment—whether those be cities, farms, or even oil fields—we can’t just plan the land we’ll occupy, we have to plan the land we won’t.

Image courtesy of Antony Lynam

Source:

Gibson L., Lynam A.J., Bradshaw C.J.A., He F., Bickford D.P., Woodruff D.S., Bumrungsri S. & Laurance W.F. (2013). Near-Complete Extinction of Native Small Mammal Fauna 25 Years After Forest Fragmentation, Science, 341 (6153) 1508-1510. DOI: 10.1126/science.1240495

Related posts:

Nature’s burning library

Ghosts of ecology

Urban forests just aren’t the same