Last week I attended an art exhibition with a unique theme—exploring climate extremes—and curator—Eli Kintisch, an MIT Knight science journalism fellow on leave from the journal Science. Kintisch has spent the last year preparing for the exhibition, called “To Extremes: Public Art in a Changing World”. Part of that preparation involved hosting what he called “Climate/Art Pizza”. The small gatherings can best be described as salons: Artists, scientists, and journalists met in his apartment here in Cambridge overlooking the Charles River to discuss how art and science intersect under the rubric of climate change. Entries to “To Extremes” followed similar guidelines.

The exhibition ended last week, but for Kintisch real challenge lies ahead. He is now working to make the winning entry—an ambitious public art installation—a reality. I caught up with him this week over email.

Tim De Chant: What inspired you to explore climate change through art?

Eli Kintisch: Data suggest that large swaths of the American public know little about climate change and have little interest in the topic. By contrast, the readers of most of my stories I strongly suspect have well-formed views on the topic, so I seek now to reach new audiences who don’t know what Science magazine is, who James Hansen is, or even that the planet has warmed 0.8 ˚C since preindustrial times.

In an age where everyone pre-filters their news with handheld computers or google news, I figure building public art will:

a) reach broad groups who don’t read science or environmental stories (and can’t run into them by chance reading a paper newspaper) and

b) use a new visual language that appeals to those who might be turned off or bored by such articles.

De Chant: Has the intersection of art and science been a longstanding interest of yours?

Kintisch: Somewhat—I first got into it in an active way when I designed this Earth Emergency Procedures Safety Card as schwag for my 2010 book Hack the Planet—on real glossy card stock. Artist Benjamin Marra, a friend of mine, helped me layout and did all the drawings, and the give and take with him, plus the challenge of making visual what I had previously described with words.

De Chant: How were the entrants judged? What was the balance between art and science?

Kintisch: To Extremes is what’s known in the art world as a juried exhibition—a fancy name for an art contest whose winners appear in an exhibition. I contacted various curators for suggestions of artists to invite, and invited 50 of them, nearly all American. More than half submitted work in the form of proposed public art works.

Those proposals were to make up the exhibition, and the jury, which included science and art experts, had to choose which pieces to go in the final exhibition. They tried to balance artistic merit with potential for impact with integrity to the science of extremes and climate. They selected nine proposals and the runner up and winner. I was truly inspired by the discussions about each piece—they really embraced the spirit of the exhibition I had created, applying their taste and expertise to choose edgy, creative but solid pieces for inclusion.

(I wasn’t on the jury, though I was present during their deliberations.)

De Chant: Why an exhibition climate extremes and not another aspect of climate change like CO2 concentration or sea level rise?

Kintisch: Mostly I pegged this exhibition with the release of the IPCC special report on extreme events, released in November ’11. I’d consider creating art competitions/juried exhibitions in the future around other aspects of climate.

De Chant: Tell me, what drew you and the other jurists to the winning entry?

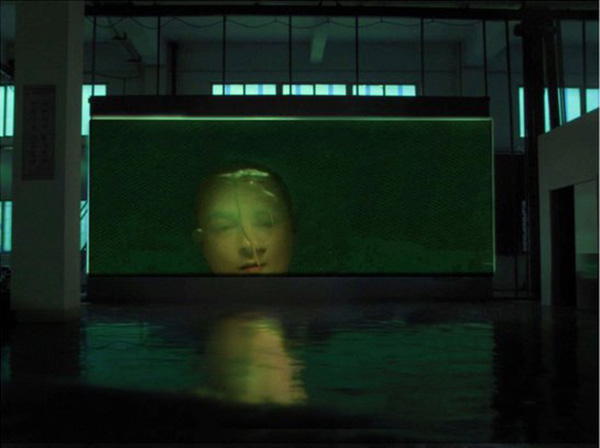

Kintisch: Sam Jury’s piece is a one-hour long video loop that explores climate adaptation in her inimitable, eerie/beautiful style. But an algorithm we are designing that responds to real-time climate data will trigger the playing of a bank of videos that explore specific extremes—i.e. extreme rain in the location of the video installation will trigger a video that visually explores the psychological and physical aspects of excess water.

The judges didn’t release a statement, but they seemed to believe Sam Jury’s piece’s a) visual beauty b) direct relevance to climate extremes and c) clever embodiment of the To Extremes theme made it the winner.

De Chant: What are the plans for the winning entry?

Kintisch: Sam Jury (who lives in Cambridge) and I spent three days last week meeting with Boston area foundations, curators, art experts and city officials to figure out how to bring her piece, which right now is just a proposal, to life. It’s audacious, no doubt: to make it work it would have to run continuously over a year or so, Sam thinks. We believe we can make it happen by tapping all the creative interest that Boston has, and our piece might even appear in other cities too.

It won’t be cheap to pull off, but a video installation would cost a lot less than other public art projects, which can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Stay tuned!