If there’s one thing that can dazzle my Western eyes, it’s the main drag of any Taiwanese town. On my recent trip to Taiwan, I saw billboards and signs for local shops that dripped from buildings with so many hues Benjamin Moore would blush. Once my mind had adjusted to the mishmash of colors, I noticed the Chinese characters, or rather their number. On each sign, there were strikingly few.

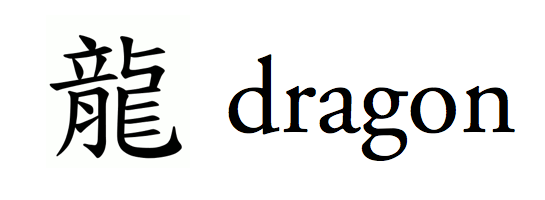

Compared with English, Chinese is a dense language. Its complex characters can convey considerable information in a very small amount of space, or where space isn’t a concern, convey that information more boldly. Given Chinese’s compact written form, I wondered how language density affected the speed at which people read.

My intuition told me that of two native speakers—one Chinese, one English—the Chinese speaker could zip through an equivalent passage in less time because each character says more. But information density can also work against a reader. Chinese’s trade-off is its complexity, both in terms of the immense number of characters—tens of thousands according to some dictionaries, though only about 4,600 are commonly used today—and the fact that nearly all of them are more baroque than any letter in the alphabet. This means someone reading Chinese must dig into the structure of each character to decipher its meaning.

Chinese characters aren’t all unique, though. Similar to English words, there are some repeating themes among them. Each character, or hanzi, consists of strokes and radicals. Strokes are single lines or curves, of which there are about 20. Radicals are constructed from several strokes, and there are about 200 of them. Characters are built by varying the presence and number of strokes and radicals. This has its advantages: proficient readers can decipher both the meaning and pronunciation of an unfamiliar character by deconstructing it. While some characters constitute an entire word, others are multiple characters strung together, much like words in English. Still, Chinese words tend to be short on average—only 1.5 characters per word, compared with 5.1 letters per word for English.

So which is more quickly read, English or Chinese? Chinese’s high information density could work for it—more complexity could impart more meaning per glance— or against it—each character could require a longer stare to decipher. The answer is neither.

English and Chinese are, by and large, read at the same speeds. In one study, both languages were read at approximately the same rate—English at 382 words per minute and Chinese at the equivalent of 386 words per minute. A statistical tie. Another study found the percentage of times a person moves backward in a text—a sign the person is having trouble processing the words—to be about the same for English and Chinese.

What simple statistics on reading speed don’t convey is how dramatically different the experience of reading is for each language. When reading English, our eyes perceive 7–8 letters a time, whereas with Chinese we perceive only 2.6 characters at once. This span—known as a saccade—multiplied by how long we fixate on it equals reading speed. Since readers of English and Chinese tend to fixate on a saccade for the same amount of time, naïve multiplication would lead you to believe that Chinese is read more slowly. After all, a reader of Chinese processes fewer characters per saccade than an English reader, and each saccade lasts about the same amount of time in both languages. But that’s only if you ignore information density. Written Chinese is dense, so though comprehension of characters is slower than letters, meaning is conveyed at the same rate as in English.

This jibes with the gist of a recent study on spoken language speed, which found that while some languages like Spanish sound faster than others, the amount of information imparted is the same. That’s because each syllable in a fast-sounding language like Spanish has less meaning than a slower one like English or Chinese. Spanish speakers have to run through more syllables to get the same point across, thus sounding faster.

Earlier linguists had suggested that Chinese might be faster to read because of a physiological quirk of our eyes—they thought the square shape of Chinese characters fit the most acute region of our retina (the fovea) better than long, string-like English words. But the authors of the first written language study I mentioned—the one that measured words read per minute—speculated that reading speed is instead limited by a cognitive bottleneck. The fact that both reading and speaking seem to follow to the same rules suggests they were right. Cognition—not language—appears to control the rate at which we communicate.

Sources:

Sun F, Morita M, & Stark LW (1985). Comparative patterns of reading eye movement in Chinese and English. Perception & Psychophysics, 37 (6), 502-6 PMID: 4059005

Sun, F, & Feng, D (2010). Eye movements in reading Chinese and English text Reading Chinese Script: A cognitive analysis, Eds. Jian Wang, Albrecht W. Inhoff, Hsuan-Chih Chen., 189-205 ISBN: 9780805824780

Yan, G., Tian, H., Bai, X., & Rayner, K. (2006). The effect of word and character frequency on the eye movements of Chinese readers British Journal of Psychology, 97 (2), 259-268 DOI: 10.1348/000712605X70066

Photo by Tim De Chant.

Related posts:

This is your brain in the city