A Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece—a house designed and built for his son—is threatened with demolition.

All posts by Tim De Chant

To Encourage Biking, Cities Lose the Helmets ∞

Elisabeth Rosenthal, writing for the New York Times:

In the United States the notion that bike helmets promote health and safety by preventing head injuries is taken as pretty near God’s truth. Un-helmeted cyclists are regarded as irresponsible, like people who smoke. Cities are aggressive in helmet promotion.

But many European health experts have taken a very different view: Yes, there are studies that show that if you fall off a bicycle at a certain speed and hit your head, a helmet can reduce your risk of serious head injury. But such falls off bikes are rare — exceedingly so in mature urban cycling systems.

She goes on to point out that helmets—and helmet laws—discourage people from riding, whether that be their own bikes or bikes from sharing programs. I think she has a good point—I crashed a few times in my younger days without a helmet and emerged unscathed, noggin-wise—but we’re a long way from undoing decades of helmet evangelism. Plus, traffic in many parts of the U.S. is anything but bike friendly. For now, I’ll be sticking with my helmet.

Parks and Re-Creation: The Revitalizing Power of Parks in Cities ∞

Ucce Agada is preaching to the choir with this one.

Massive shrinkage in African great ape habitat since 1990s ∞

Leigh Phillips covers the results of a new study published last week that show it’s not a good time to be a great ape (well, a great ape other than Homo sapiens).

Do Rankings Affect Our Opinions of Cities? ∞

Samuel Arbesman, writing earlier this year for the Atlantic Cities:

While certain cities are positively viewed by all regions, each region has a better view of its own cities than those cities of other regions. The South likes southern cities, the West western cities, and so forth. The Midwest appears to be the most self-hating (or at least the least positive toward itself) of the Census regions.

We Midwesterners have always been humble to the point of self-deprecating. But I wouldn’t read to much into this—we also have a lot of pride in our hometowns, too. If anything, we’re just really good at identifying how our cities’ could be better.

Bus rapid transit apes trains to attract riders ∞

PSM reader Michael Kenny points to this article in the Wall Street Journal on bus rapid transit, or BRT. For the unfamiliar, BRT lines are served by standard or extended-length buses and have various advantages over traditional bus lines—fewer stops, nicer shelters, signal priority, and reserved lanes. They’re typically cheaper than light rail, too. But there’s one drawback that’s seldom mentioned—it’s far easier to water down a BRT proposal by doing away with reserved lanes and improved shelters, making BRT less appealing to riders.

Still, as Kenny notes, BRT can help extend transit to cities and communities that might not have the money for rail. You’ve got to start somewhere.

Apple's Maps takes a page from Google's playbook ∞

Dylan Tweney linked to this 2009 post by venture capitalist Bill Gurley in which Gurley dissects Google’s then-recent introduction of turn-by-turn directions:

To understand just how disruptive this is to the GPS data market, you must first understand that “turn-by-turn” data was the lynchpin that held the duopoly together. Anyone could get map data (there are many free sources), but turn-by-turn data was remarkably expensive to build and maintain.

By adding turn-by-turn directions to Android, Google essentially pulled the rug out from under TomTom (which bough Tele Atlas for $2.7 billion in 2007) and Nokia (which had acquired NavTeq for $8.1 billion that same year).

Tweney states that Google’s strategy then “illuminates Apple’s maps strategy now”. Apple is now offering their users a previously “free” service for free. I use quotes there because Google’s mapping services are “free” in that you don’t pay to use them, but they still demand a price—your privacy. Location factors hugely into advertising these days, and Google is first and foremost an ad company. Apple is not.

In moving mapping in-house, Apple has killed three birds with one stone—they are no longer dependent on a competitor for a core feature, they’re denying that competitor access to valuable data, and they’re taking a stand for people’s privacy.

Gurley finishes:

Another perhaps even more important factor is that when a product is completely free, consumer expectations are low and consumer patience is high. Customers seem to really like free as a price point. I suspect they will love “less than free.”

The problem for Apple is that consumer patience at this point is low, and they’ve knocked so many out of the park that expectations are high. Fixing that imbalance will require Apple to convince users that their maps are superior. Or to actually make them so.

A letter from Tim Cook on Maps ∞

Apple offers a mea culpa on the new Maps app’s shortcomings. Good on them for admitting it, and even more kudos for suggesting other apps people can use until Maps is back up to snuff.

In the meantime, I think I’ll keep using the official Maps app. It’s not perfect, but I’ve been using it heavily this past week and I don’t think it deserves the drubbing it’s received on the web.

Louisville embraces the interstate, again ∞

Freeway-free urbanism may be in vogue in cities across the U.S., but not, apparently, in Louisville, according to Michael Kimmelman:

So what is Louisville doing now?

Pursuing a plan that would, in part, enlarge the downtown highways and construct a second bridge next to the Kennedy. It would even eat up some of a park designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, of Prospect Park and Central Park fame. Louisville is a car city with auto plants and a big investment in the auto industry. But still, I was stunned to hear this. The proposal, so clearly out of step, has been met with grass-roots opposition and is now in the courts, tied up over issues about financing, tolls and the environment.

How Google Builds Its Maps—and What It Means for the Future of Everything ∞

Alexis Madrigal, with a fantastic, comprehensive look behind the curtain at Google Maps:

Behind every Google Map, there is a much more complex map that’s the key to your queries but hidden from your view. The deep map contains the logic of places: their no-left-turns and freeway on-ramps, speed limits and traffic conditions. This is the data that you’re drawing from when you ask Google to navigate you from point A to point B — and last week, Google showed me the internal map and demonstrated how it was built. It’s the first time the company has let anyone watch how the project it calls GT, or “Ground Truth,” actually works.

The Shirt ∞

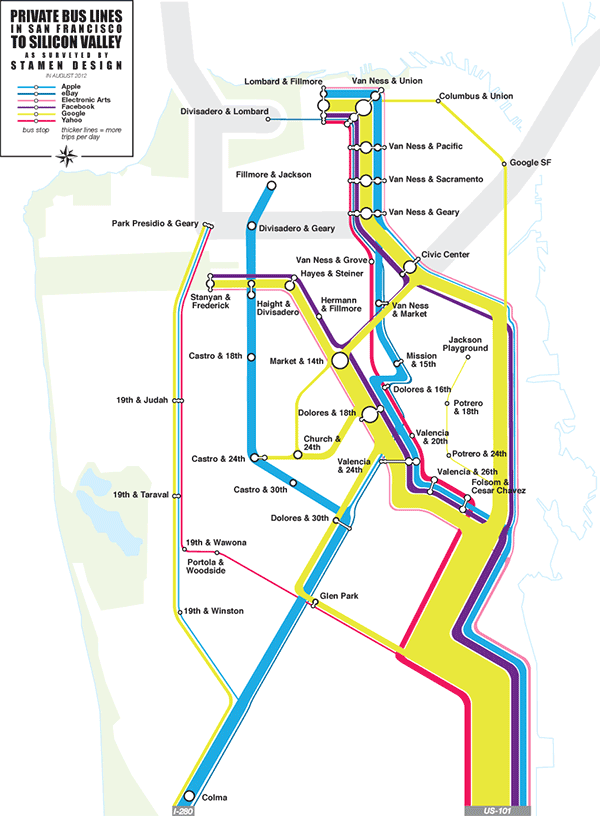

Where to catch the Google bus ∞

Mass transit is often—and often rightfully—conflated with public transit. But in reality, the open-to-everyone variety is a subset of mass transit. It’s a fact that’s well-known to select San Franciscans—those who work in Silicon Valley. Every morning and evening, private buses criss-cross the city, hauling these commuters to and from their jobs. It’s a shadow transit network that, despite operating in plain sight, isn’t public knowledge. Or at least wasn’t. Stamen Maps used data from Foursquare and bus companies to plot the routes in the style of a traditional transit map. Now you can see where the Google bus picks up. Just don’t expect to hop onboard with $2 and some change.

Geography of back-to-school ∞

Sarah Rich:

Growing up in Denver, I called sugary, carbonated beverages “pop.” When I moved to California for college and all the coastal kids called it “soda,” I realized just how much geography defines even the most quotidien bits of our lives (I now call it “soda,” too.). I had that realization all over again recently while reminiscing about Pee-Chee folders, encountering a completely blank stare from a New York-native friend who had never heard of them. And here I’d thought the pulpy paper pockets had been a part of every American’s back-to-school memories.

Another point on the map: We never had Pee-Chee in southeastern Wisconsin, either. Still, it’s always fun to examine geographic lexicography.

Growing Power scores $5 million to feed our nation’s hungriest cities ∞

Proud to say this nonprofit started in Milwaukee. Genius Will Allen is really pushing the envelope.

Trains of Tomorrow, After the War ∞

Matt Novak:

American advertisers made a great number of promises for the future during World War II. The American people were told that if they could just be patient with wartime rationing, or the number of resources being devoted to the war effort, we would all be assured better lives after the war.

The Association of American Railroads was no different, and in the March 18, 1944 issue of Collier’s magazine they ran an ad which promised great things in train travel after World War II was through. It’s interesting for those of us perched from the vantage point of the future to remember that other methods of transportation, such as commercial air travel and even automobiles, weren’t the established forms that they would later become.

Reminiscent of Boeing’s and Airbus’s mockups of their latest planes, which often show their wares outfitted with some extravagance that most of us will never experience. Usually, such fantasies are quickly sacrificed at the altar of expense—the transportation industry is about moving things, and hauling empty space doesn’t pay as well. Still, they make for great ad copy.

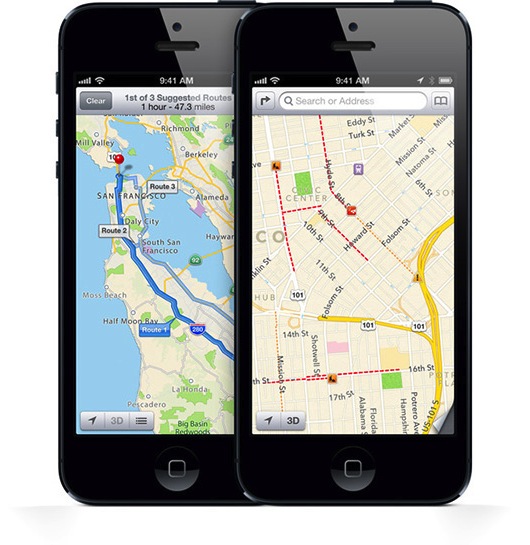

Searching for the truth in Apple’s Maps

Last week Apple released iOS 6. Along with the usual bevy of new features and refinements, the company made one change that’s drawn some ire. The built-in Maps app ditched Google as its data source, instead relying on information from Apple’s own servers. Apple has doubtless been preparing for the change for years, but that didn’t mean the transition was smooth. In fact, it was anything but.

I can attest to that from first-hand experience. I managed to snag one of the last iPhone 5s in Cambridge last Friday. To be sure, it’s a gorgeous device—for some reason the tall screen combined with its thin profile make me feel like I’m holding an artifact of the future. But that also meant I was forced to run iOS 6 and use Apple’s own maps.¹ The software behind the new Maps app is slicker and snappier than before, as I predicted a few months ago, but no one ever doubted that Apple could write some killer software. The concern was over the data. Could Apple build a GIS as complex and detailed as Google in just a few years? In short, no.

But for all the inconvenience this will bring in the short-term, I still think Apple’s move away from Google was the right move. For everyone involved, users included. The importance of Apple’s Maps isn’t that it snubs a competitor or that it now provides turn-by-turn directions. No, Apple’s in-house solution is significant because it serves as a cartographic foil to Google’s Maps.

Compared with the Google Maps of today, Apple’s shortcomings are obvious. The lack of transit directions is problematic,² many addresses are misplaced, and its routing algorithms need some tweaking. As a 1.0, though, Apple’s Maps compares favorably with Google Maps circa 2005. Back then, there was no street view, no hybrid view, no API for developers. But it’s not 2005, it’s 2012. If Google’s excellent maps had never existed, we’d be heralding our new cartographic savior. But years ago Google showed us how useful good maps can be. We’ve already seen the light.

And we love it. Google’s interface is slick and responsive. Their experience in search means queries return useful results more often than not. The company has spent years polishing its maps, adding insane amounts of detail, revealing secrets even we didn’t know about our own neighborhoods. As a result, Google Maps has become the de facto source for web maps.

But that dominance poses a problem. Too often, we assume that maps are pictographic snapshots of the world around us. But we forget that they paraphrase the real world. Maps abridge things here, gloss over details there, and otherwise simplify the world. Someone has to decide what gets left out. Whether it’s one person or an entire company making those decisions, the potential for manipulation—intended or not—is high. Everyone has their own biases, and Google’s is advertising. As a result, businesses can pay to alter the map. It’s a subtle reminder that maps aren’t purely factual—they’re facts filtered through a worldview.

That’s not to say Apple’s cartographers and programmers don’t have their own biases. But the added competition will keep Apple, Google, and others more honest. For now, it’s Apple that needs to catch up; their maps are clearly lacking. Yet there may be a time when Apple’s maps exceed Google’s in quality, forcing the search giant to reconsider how it gathers and displays information, including ads. There will never be a map that everyone considers 100 percent correct, but the more competition, the closer we’ll get. In the long run, that benefits everyone.

- Yes, I could have used Google’s web interface in a pinch, but it’s not as elegant and I wanted to put the new Maps app through its paces. ↩

- I used transit heavily over the weekend, and I can tell you that third-party apps are no panacea. Apple’s going to need to incorporate transit data sooner than later. It’s my guess that, once they iron out the thousands of agreements with as many agencies, they will. ↩

Photo from Apple.

San Francisco fog, as seen from space ∞

I have many memories of San Francisco’s fog, both comforting and dismaying (especially on summer evenings, when the thick blanket of moisture swiftly erased all warmth of a fine summer day). This image, taken by NASA’s Advanced Land Imager on the EO-1 satellite, captured a relatively clear day, by San Francisco standards. Another curiosity: The fingers of fog stretching across the bay are reaching north for Richmond instead of due east for Berkeley, a more usual target in my experience.

Why neighborhood quality matters

In the summer of 2008, I found myself lost in Chicago. I was new to the sprawling city, living there for two months while working as an intern science reporter at the Chicago Tribune. To counter weekend boredom, I would explore the city by bike. I’d often find myself mildly disoriented, but this time I had really done it. I knew I was north of the Loop, but that was about it.

Finally, I happened across Halsted Street, a major north-south thoroughfare that ran a few blocks from where I was living. Relieved, I started south, coasting past nice brick apartment buildings and row houses, big box stores and tony shops. But after a few miles, the timbre of Halsted changed. Quickly. Well-kept storefronts gave way to crumbling industrial buildings and weedy sidewalks. Then came the most depressing hulk of a building you could imagine. It was a drab beige tower surrounded by acres of asphalt and dotted with boarded up windows fringed with smoke stains. I knew exactly where I was.

Cabrini-Green’s bad reputation was well-known, especially in the Midwest where I grew up. It was among the first projects built by the Chicago Housing Authority in the mid-20th century. By the 1970s, Cabrini-Green was notorious for destitution and violence. Gangs had taken over various buildings, and internecine warfare kept even the hard-nosed Chicago police at bay. Tales of horrific murders spread around the country. My aunt, who tutored elementary school students there, would recount stories she heard from residents. Cabrini-Green was at best a place to be avoided.

And here I was, blithely riding by. Though I didn’t know it at the time, Cabrini-Green’s most notorious days were past it. The tower was largely vacant, save for a few holdouts. When I moved back to Chicago a year later, the last of the high-rises were being torn down.

Housing projects are widely viewed as a failure. Their concentrated poverty seemed to descend into a negative feedback loop, where depravity fed on itself. Over the years, Chicago tried to assert control, to no avail. They muscled up the police presence; that was met with sniper fire. In 1981, then-mayor Jane Byrne moved into a ground floor apartment guarded round the clock by uniformed officers. She moved out three weeks later.

Oddly enough, Byrne’s publicity stunt was on the right track, if completely backwards. Housing projects’ needed a shock to break the cycle. But they didn’t need a mayor moving in. They needed to move people out.

That’s exactly what the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development did in the mid-1990s, when it took over the dysfunctional Chicago Housing Authority. As a part of the Moving to Opportunity program, households could enroll in a lottery which would give winners assistance in finding and vouchers to pay for housing in low poverty neighborhoods. Chicago wasn’t the only city in the trial—New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and Baltimore were also involved. The idea was that after moving to low poverty neighborhoods, families would find more and better jobs and be healthier and happier. Nearly 5,000 families were included in the experiment.

It worked, to some extent. A study published today in the journal Science details how people involved in Moving to Opportunity have fared in the 15 years since the program started. Though those who moved to low poverty neighborhoods were still as poor as those who didn’t, there were some changes. Notably, they were happier and somewhat healthier.

The study, led by Jens Ludwig of the University of Chicago, looked at a variety of factors, ranging from poverty rate to racial segregation to mental and physical health. Though poverty rates didn’t change significantly, and racial segregation nudged only slightly lower, people’s health improved. Physical health, as measured by obesity and diabetes, were slightly better in this study. (A prior study published by Ludwig and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine last year reported more significant improvements.) But mental health, as measured by self-reported subjective well-being, or how people felt about their lives, was significantly improved among people who lived in low poverty neighborhoods. So while people were still poor, they were happier. That says a lot about the importance of your surroundings.

Ludwig and his colleagues point out that if the objective of Moving to Opportunity was to reduce poverty, then at this point it would be considered a failure. But if the goal was to improve people’s lives in other ways, well, it’s not doing too bad.

The study only focused on adults, in part because measuring subjective well-being of youngsters is an inexact science. Because of that, they’re missing an important component. It’s difficult to break free of poverty, especially when you’ve inherited it. But children, through better education and improved health, have more potential than their parents (even if that’s only because they have more of life left to live). It’s possible that, because of a more positive home life, kids in families living in low poverty will have better opportunities than their parents, helping them break the cycle.

Source:

Ludwig, Jens, Greg J. Duncan, Lisa A. Gennetian, Lawrence F. Katz, Ronald C. Kessler, Jeffrey R. Kling Lisa Sanbonmatsu. 2012. “Neighborhood Effects on the Long-Term Well-Being of Low-Income Adults”. Science 337(21): 15051510. DOI: 10.1126/science.1224648

Photo by puroticorico.

Related posts:

A new way to measure income inequality ∞

Jeff Horwich of the public radio show Marketplace, interviewing yours truly on trees and income inequality hot on the heels of a new Census report showing income inequality in the United States is on the rise. (Before this new report, we knew it was already higher than in the ancient Roman Empire.)

Thanks to Jeff and assistant producer John Ketchum for having me on.

Can city life be exported to the suburbs? ∞

Jonathan O’Connell, reporting for the Washington Post on “town centers”, the latest rage in retail development:

By the end of 2011, there were 398 such city replicas — town center or “lifestyle center” projects — in the United States, most of them built in suburbs, in exurbs or on farmland alongside a highway. Since the 1960s, developers had promoted suburban shopping centers as safe, clean escapes from crowded cities. But with urban living back in vogue since the late 1990s, developers are trying to create it outside city limits.

These sort of places give me the creeps. It’s not just the faux urban feel they exude—it’s because they’re privately owned, right down to the streets, sidewalks, and parks. Want to put together a new farmer’s market? Better go through the PR department. Want to organize a protest or other gathering? Good luck. And you can’t vote to change it, either. To me, downtown should be the center of a community, not another line in a corporate balance sheet.