Know someone who might like a Per Square Mile membership? The drive is still on for a few days more.

Sometimes highways are beautiful ∞

Emily Badger rounds up some pretty cool visualizations of GPS tracks from automobile traffic over highways.

Did Cars Save Our Cities From Horses? ∞

Brandon Keim, reporting for Nautilus:

History loves smooth transitions, such as horses to cars. “There’s an assumption that you have this clean break between eras,” says urban historian Martin Melosi. “In the real world, that doesn’t happen.” The idea of a neat transition from horses to the automobile age is a history-as-approved-by-victors myth that elides several decades when horse travel declined but automobiles were uncommon, used primarily to haul freight. The automobile as we now conceive it, a personal transport machine, wouldn’t come along for nearly half a century.

Good and Bad News for Endangered Species in the Latest "Red List" Update ∞

Victoria Turk, writing for Motherboard:

There’s positives and negatives in the most recent update to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, which tracks endangered organisms. While we humans are still generally driving the world’s largest extinction event since the dinosaurs met their fate, we’re also seeing some positive feedback from our (admittedly not nearly equivalent) conservation efforts.

NYT confirms drop in environment coverage ∞

Margaret Sullivan, the New York Times’ public editor, reports that quantity, quality, and depth of coverage on environmental stories has declined since the paper dismantled its environment desk.

Bulk retailing goes virtual ∞

Christopher Mims, reporting for Quartz:

Unlike most of Silicon Valley, which seems obsessed with multi-billion-dollar valuations for whatever ephemera the kids are into these days, Boxed moves just as many atoms as bits. It’s an online store that, like Amazon, will deliver whatever you buy to your door—but only in bulk. If Amazon is the online Walmart, Boxed is the online Costco.

Another nail in big-box retailing’s coffin.

Why I Make Terrible Decisions, or, poverty thoughts ∞

A powerful piece, posted on Kinja:

Rest is a luxury for the rich. I get up at 6AM, go to school (I have a full courseload, but I only have to go to two in-person classes) then work, then I get the kids, then I pick up my husband, then I have half an hour to change and go to Job 2. I get home from that at around 1230AM, then I have the rest of my classes and work to tend to. I’m in bed by 3. This isn’t every day, I have two days off a week from each of my obligations. I use that time to clean the house and soothe Mr. Martini and see the kids for longer than an hour and catch up on schoolwork. Those nights I’m in bed by midnight, but if I go to bed too early I won’t be able to stay up the other nights because I’ll fuck my pattern up, and I drive an hour home from Job 2 so I can’t afford to be sleepy. I never get a day off from work unless I am fairly sick. It doesn’t leave you much room to think about what you are doing, only to attend to the next thing and the next. Planning isn’t in the mix.

Just 90 companies caused two-thirds of man-made global warming emissions ∞

Suzanne Goldberg, reporting for the Guardian:

The climate crisis of the 21st century has been caused largely by just 90 companies, which between them produced nearly two-thirds of the greenhouse gas emissions generated since the dawning of the industrial age, new research suggests.

The companies range from investor-owned firms – household names such as Chevron, Exxon and BP – to state-owned and government-run firms.

The analysis, which was welcomed by the former vice-president Al Gore as a “crucial step forward” found that the vast majority of the firms were in the business of producing oil, gas or coal, found the analysis, which has been published in the journal Climatic Change.

What landscape architects do at home ∞

Michael Tortorello, profiling landscape architect Thomas Ranier’s home garden:

You envision a garden from on high: In the trade, this exalted perspective is called “plan view.” But you dig and plant at ground level with the stuff you have. For all his training and vision, then, Mr. Rainer’s yard is a lot like everyone else’s: a compromise.

It is a three-dimensional equation of compromise, actually, where the X axis is taste, the Y axis is money and the Z axis is time. To be specific, Mr. Rainer has an overabundance of X, a scarcity of Y and, hold on, where did all the Z go?

How to keep the economy growing when our population is not

Zero population growth is a period in future human history that is both hoped-for and feared. If we don’t get to that point, the world could literally become overrun with humans, straining already taxed resources like fresh water and farmland to the breaking point. But with zero population growth, the global economy—heavily reliant on a young and expanding workforce—could collapse. No matter what we hope, according to projections by the United Nations, it’s likely that within the next century, the global population will level off or even shrink.

It’s a prospect that vexes demographers and economists alike, which is a sharp change from the 1960s, when we feared rampant population growth. Now, we fret over the opposite, and for good reason. While stabilizing or declining numbers will certainly ease the burden on the environment, no one knows how society will function in a future with fewer people. Globally, it’s never happened before. Locally, we’re starting to see it in some countries such as Japan, which has been stuck at about 127 million for the last decade. By 2045, it will drop to 105 million, and it’s already affecting Japan’s long-term thinking—some economists are questioning the need for the country’s proposed maglev system if there are fewer people to ride it.

There’s another, more fundamental problem that zero or negative population growth poses, though—the transfer of knowledge. We know that when people come together, they tend to create new technologies, skills, and knowledge. Cities are hubs of innovation, universities are great factories of scholarship, and even smaller groups can inspire people to create wonderful things. Perhaps more importantly, the number and strength of our connections are vital for passing knowledge on to others, two recent studies suggest. Without those connections, our society could fall rapidly behind. Fortunately, the research also suggests a way to escape the declining population trap.

Ed Yong, who covered the two studies for Nature News, pointed out that the papers provide independent validation of the idea that cultural knowledge is tightly correlated with group size and connectedness. They approach the problem from slightly different angles. The first study examined whether group size affected how well cultural tasks—in this case making an arrowhead or a fishing net—were passed down from one group to the next. In every instance, groups of eight or 16 performed significantly better than groups of two or four. Bigger groups also developed better and quicker ways of making the arrowheads.

The second study tested how interpersonal connections affected performance of a task, in this case either duplicating an image on a computer or recreating a series of knots used in rock climbing. In the drawing experiment, which tested the creation of knowledge, inexperienced people started off, going by trial and error. Later generations of participants could watch earlier people’s attempts and use that to hone their skills. Some were given the opportunity to observe five different attempts, others were only given the chance to see one. Those who had access to five examples recreated the drawings more accurately than those who could only see one.

The knot-tying experiment tested how cultural knowledge was maintained. The first generation of participants was trained by an instructor. Later generations watched footage of previous people tying the knots. Those who could watch five examples were twice as good at tying the knots as those who could only watch one example. The more connections, the more faithfully that knowledge was passed on.

Together, these two papers make a strong case for social savvy being the foundation of our complex culture. The first paper—the one with the arrowheads and fishing nets—confirms experimentally what many scientists suspected, that larger groups are both more proficient and more innovative. But the second study really intrigues me. It’s the one that, I believe, offers a way to keep our economy surging when our population begins to level off or decline.

The key to that is social connections. The more connected people were in either experiment of the second study, the better they performed, whether that be for maintaining knowledge or advancing it. Following that thread, it stands to reason that we can successfully decouple economic growth from population growth if social connections continue to increase. So even if our numbers decline, as long as our connections do not, we will at the very least be able to maintain our cultural knowledge and hopefully our standard of living.

To do that, we need to meet three challenges. First, the trend toward urbanization needs to continue. Cities foster connections between people, and the more people that live in cities, the more cultural knowledge we can maintain. Second, the internet needs to be everywhere. As the internet has taken hold, it has connected people in ways never before imagined. It’s now easier to access scholarly articles, stay in touch with friends and family, and partner with peers around the globe, all of which serve to maintain and increase our collective knowledge. Finally, as cities swell, we need to make sure they are physically connected as seamlessly as possible. Large cities can provide a wealth of opportunities, but no single city can offer them all. Being able to zip from one to the next will be vital for our cultural survival.¹

If we can meet those three challenges, and if social connections continue to multiply as population stabilizes or declines, then I think we’ll have a good chance of maintaining economic growth and raising standards of living.

- I would argue that this implies that Japan’s maglev system will be even more important if the population declines as is predicted. They’ll need more connections, not fewer. ↩

Sources:

Derex M., Beugin M.P., Godelle B. & Raymond M. (2013). Experimental evidence for the influence of group size on cultural complexity, Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature12774

Muthukrishna M., Shulman B.W., Vasilescu V. & Henrich J. (2013). Sociality influences cultural complexity, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281 (1774) 20132511-20132511. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2511

Photo by eioua

Related posts:

Population density fostered literacy, the Industrial Revolution

If the world’s population lived like…

Hunter-gatherer populations show humans are hardwired for density

Less than two weeks remaining… ∞

The current Per Square Mile membership drive ends in less than two weeks, so be sure to get your orders in soon. There are two ways to support Per Square Mile—buy an all-new t-shirt for $29, including shipping, or contribute $19 or more.

Proceeds go to support outdoor programs for kids through the Children and Nature Network.

Japan Pitches Its High-Speed Train With an Offer to Finance ∞

Eric Pfanner, reporting for the New York Times:

To build the proposed American line, Japan has come up with a method of financing that is similarly novel. In a meeting with President Obama last winter, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe offered to provide the maglev guideway and propulsion system at no cost for the first portion of the line, linking Washington and Baltimore.

“We are going to share this technology with the United States because the United States is our indispensable ally,” said Yoshiyuki Kasai, chairman of the Central Japan Railway Company, which runs the maglev test track and is building the Tokyo-Osaka line.

Officials have not placed a dollar figure on the value of the aid but say it would cover close to half of the overall cost of construction. Based on the estimated cost of the maglev line from Tokyo to Osaka, which is more than $300 million per mile, that means the Japanese financing could be worth about $5 billion.

The financing can be viewed as either a savvy incentive or international aid, depending on your perspective.

Walmart store has its own food bank for poor employees ∞

Olivera Perkins, reporting for the Cleveland Plain Dealer about an Ohio Walmart store:

“Please Donate Food Items Here, so Associates in Need Can Enjoy Thanksgiving Dinner,” read signs affixed to the tablecloths.

The food drive tables are tucked away in an employees-only area. They are another element in the backdrop of the public debate about salaries for cashiers, stock clerks and other low-wage positions at Walmart, as workers in Cincinnati and Dayton are scheduled to go on strike Monday.

Is the food drive proof the retailer pays so little that many employees can’t afford Thanksgiving dinner?

Most of the world’s solar panels are facing the wrong direction ∞

Christopher Mims, writing for Quartz:

You’d think it would be easy: the sun is “up,” and, like leaves and basking reptiles, solar panels should face in that general direction. But most installers of solar panels, especially the ones for homes, follow conventional wisdom handed down from architects, which holds that in the northern hemisphere, windows and solar panels should face south.

This makes intuitive sense since it would seem to maximize the amount of sunlight a panel will get as the sun tracks from one horizon to the other. But it isn’t true, at least according to a single study of homes in Austin, Texas. The Pecan Street Research Institute found that homeowners who aimed their panels toward the west, instead of the south, generated 2% more electricity over the course of a day.

Auto Correct ∞

Buckherd Bilger, reporting for the New Yorker with a bit of history on self-driving cars:

Almost from the beginning, the field divided into two rival camps: smart roads and smart cars. General Motors pioneered the first approach in the late nineteen-fifties. Its Firebird III concept car—shaped like a jet fighter, with titanium tail fins and a glass-bubble cockpit—was designed to run on a test track embedded with an electrical cable, like the slot on a toy speedway. As the car passed over the cable, a receiver in its front end picked up a radio signal and followed it around the curve. Engineers at Berkeley later went a step further: they spiked the track with magnets, alternating their polarity in binary patterns to send messages to the car—“Slow down, sharp curve ahead.” Systems like these were fairly simple and reliable, but they had a chicken-and-egg problem. To be useful, they had to be built on a large scale; to be built on a large scale, they had to be useful. “We don’t have the money to fix potholes,” Levandowski says. “Why would we invest in putting wires in the road?”

Smart cars were more flexible but also more complex. They needed sensors to guide them, computers to steer them, digital maps to follow. In the nineteen-eighties, a German engineer named Ernst Dickmanns, at the Bundeswehr University in Munich, equipped a Mercedes van with video cameras and processors, then programmed it to follow lane lines. Soon it was steering itself around a track. By 1995, Dickmanns’s car was able to drive on the Autobahn from Munich to Odense, Denmark, going up to a hundred miles at a stretch without assistance. Surely the driverless age was at hand! Not yet. Smart cars were just clever enough to get drivers into trouble. The highways and test tracks they navigated were strictly controlled environments. The instant more variables were added—a pedestrian, say, or a traffic cop—their programming faltered. Ninety-eight per cent of driving is just following the dotted line. It’s the other two per cent that matters.

A Neuroscientist’s Radical Theory of How Networks Become Conscious ∞

Brandon Keim interviewed neuroscientist Christof Koch, who theorizes that consciousness arises in any network that’s highly connected and highly complex. There are the usual artificial intelligence related questions, but then there’s this:

WIRED: Ecosystems are interconnected. Can a forest be conscious?

Koch: In the case of the brain, it’s the whole system that’s conscious, not the individual nerve cells. For any one ecosystem, it’s a question of how richly the individual components, such as the trees in a forest, are integrated within themselves as compared to causal interactions between trees.

The philosopher John Searle, in his review of Consciousness, asked, “Why isn’t America conscious?” After all, there are 300 million Americans, interacting in very complicated ways. Why doesn’t consciousness extend to all of America? It’s because integrated information theory postulates that consciousness is a local maximum. You and me, for example: We’re interacting right now, but vastly less than the cells in my brain interact with each other. While you and I are conscious as individuals, there’s no conscious Übermind that unites us in a single entity. You and I are not collectively conscious. It’s the same thing with ecosystems. In each case, it’s a question of the degree and extent of causal interactions among all components making up the system.

Japan Shelves Plan to Slash Emissions, Citing Fukushima ∞

Hiroko Tabuchi and David Jolly, reporting for the New York Times:

Under its new goal, Japan, one of the world’s top polluters, would still seek to reduce its current emissions. But it would release 3 percent more greenhouse gases by 2020 compared to levels in 1990. Japan’s previous government had promised before the Fukushima crisis to cut greenhouse emissions by 25 percent from 1990 levels, expecting that it could rely on nuclear power to achieve that goal.

Since the 2011 disaster, Japan’s nuclear power program, which provided about 30 percent of the country’s electricity, has ground to a halt amid public jitters over safety. The current government is pushing to restart reactors, but it remains unclear when that might happen.

“We’re down to zero nuclear; anyone doing the math will find that target impossible now,” Nobuteru Ishihara, the environment minister, said in Tokyo after announcing the new target.

What Would A Hyperloop Nation Look Like? ∞

Katie Peek and Michael Kelly put together an infographic over at Popular Science that hypothesizes what nation-wide hyperloop network might look like and how long it would take to travel to another city via the crazy tube cars.

How cities change the weather

Late in the day on June 13, 2005, a thunderstorm was bearing down on the city of Indianapolis. As the main cell approached from the southwest, it reared up, convection currents pushing it higher and higher until it towered over the city. Luckily for Indianapolis, the cloud threatened more than it menaced, eventually dumping just an inch of rain on suburbs and farm fields to the northeast. On the surface, it may not have seemed particularly special. But for meteorologists studying the storm, it was perfect.

What set that storm apart from others, they suspected, was the fact that it passed over Indianapolis. The fact that the city was there—the subtle but significant change it made to the texture and composition of the Earth’s surface—was enough to alter the structure of the storm. Using a model they built to test the city’s impact, meteorologists couldn’t accurately simulate the June 13 storm without Indianapolis.

Humans altering the weather is the stuff of science fiction. (Not climate, mind you. That’s unfortunately all too real.) Not that we haven’t tried—cloud seeding, while not as promising as once thought, is still used on occasion to coax more precipitation from the sky or to wring clouds dry, as was the case during the Beijing Olympics. Cloud seeding is small scale stuff, though, and the amount of effort required makes it unsustainable over the long term. But while tactical, widespread weather control remains beyond our grasp, we routinely change the weather around the world simply by living in cities. And most of us don’t even know it.

The most common—and well known—way that we change the weather is through the urban heat island effect. In an urban heat island, a city’s mass of asphalt and concrete and lack of tree cover traps and holds heat. That effect may drive other shifts in the weather, including the change in structure of the June 13th storm over Indianapolis. Heat rising off a city, meteorologists think, increases convection within storms, pushing the storm cloud higher faster and raising its reflectivity core, or the size and distribution of rain droplets within the cloud. In some cases, cities can even split the reflectivity core—the buildings exert drag on the atmosphere, which disrupts the storm’s airflow.

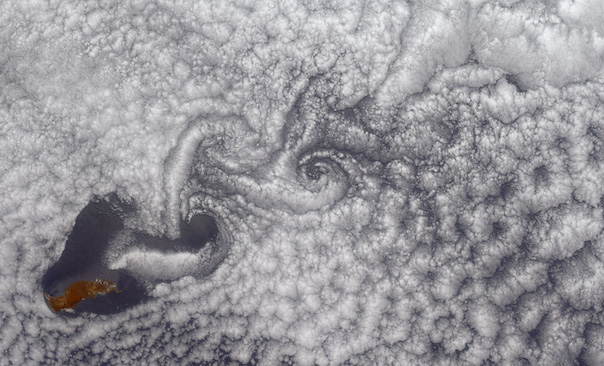

That a city’s physical structure can affect a massive system like a thunderstorm may seem unlikely, but it’s not improbable. Scores of satellite images have captured islands cleaving clouds, creating successive swirls downwind, a phenomenon known as the Von Karman effect. No one has seen cities create disturbances as charismatic as the Van Karman effect, but Marshall Shepherd, a professor at the University of Georgia and president of the American Meteorological Society, told me that one of his students has found traces of it in his research models. Unfortunately, the results weren’t strong enough to include in a publication.

Apart from changes in cloud structure, there’s also some evidence that cities change the amount of rainfall a storm produces. A large field experiment carried out in North America in the 1970s, known as METROMEX, concluded that cities increased cumulative precipitation by 5-25 percent, most of which fell downwind of the city. Size mattered, too. Bigger cities tended to induce more rainfall that fell over a larger area. Since then, some studies have disagreed, claiming there’s no change, but an even larger number seem to confirm the patterns found in METROMEX. Depending on the region, these new studies found that cities may increase rainfall by up to 60 percent, several-fold more than previously thought. What’s causing that? Any number of factors, including aerosols from pollution, the urban heat island, and changes in airflow over buildings, could be driving the urban rainfall effect. But to date, no one can definitively explain why it occurs.

When you add it all up—and throw in a few other variables I haven’t discussed, including lightning strikes and wind speeds—it’s clear that cities have an undeniable impact on the weather. That many of those effects extend far beyond political boundaries should only reinforce the idea that cities and their countrysides are inextricably linked.

Sources:

Shepherd J.M. (2013). Impacts of Urbanization on Precipitation and Storms: Physical Insights and Vulnerabilities, Climate Vulnerability: Understanding and Addressing Threats to Essential Resources, 109-125. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-384703-4.00503-7

Niyogi D., Pyle P., Lei M., Arya S.P., Kishtawal C.M., Shepherd M., Chen F. & Wolfe B. (2011). Urban Modification of Thunderstorms: An Observational Storm Climatology and Model Case Study for the Indianapolis Urban Region, Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 50 (5) 1129-1144. DOI: 10.1175/2010JAMC1836.s1

Related posts:

Invasion of the ladybugs ∞

In the last decade or so, Midwest autumns have become punctuated by more than just falling leaves—they’ve been invaded by swarms of Asian ladybugs. Introduced to prey on crop pests, the native ladybug doppelgägners have become somewhat of a pestilence themselves, coating entire walls of buildings, as they did to one house I lived in during college.

But there’s more to these little red dots than I had given them credit for, as David George Haskell discovered:

These beetles may quite literally have a silver lining. Their ecological success is partly due to their invulnerability to disease, a super-power conferred by their ”hemolymph” (insect blood). The potency of this vital essence is easily confirmed: poke a beetle and see the defensive yellow ooze of blood emerge from chinks in their legs, staining your hand and releasing a powerful odor. Studies of the antimicrobial properties of the blood show that it contains a chemical, harmonine, that inhibits both TB and malaria. Knowing this, I pick the ladybugs out of my hair with new found respect and even a sense of hope that medical wonders may yet emerge from the entomological onslaught.