There’s a scene in the movie Office Space where Peter, the protagonist, unscrews part of his cubicle and ceremoniously pushes the wall over, sending it and its shelved contents crashing to the floor. With a satisfied smile, he pats his desk a few times, kicks back, and enjoys his new view.

As I write this, the view out my window isn’t much more than Peter’s. Just a handful trees—no mountains, no idyllic nature scene, nothing that would make Ansel Adams jealous. Just one scrubby street tree and a couple of canopies poking their heads above the adjacent apartment building.

But according to Rachel Kaplan, an environmental psychologist, those few trees are far better than nothing at all. Kaplan has documented numerous cases in which workers reported feeling happier and more satisfied with their jobs because of the view they had out their window. Even views of parking lots—so long as they had trees or some other landscaping—were enough to brighten some people’s days.

Kaplan has made a career out of studying how views of nature affect various parts of people’s lives, from patient recovery times to worker productivity. Currently, I’m interested in her research on the latter topic. Staring out at a busy street is better than no view at all, but sometimes I feel antsy and distracted for no apparent reason. I’ve wondered if a more bucolic view would focus my efforts and lift my spirits. Coincidentally, Kaplan’s research suggests that’s exactly what would happen.

Kaplan says windows give people the opportunity for short restorative breaks. After hours spent staring at a computer screen or hammering through some repetitive task, a brief diversion or daydream is sometimes all that’s needed to push through the rest of the day. Allowing ourselves a short mental break boosts our happiness, which also increases our productivity.

But restorative breaks are more effective, according to Kaplan’s research, if they include gazing upon a natural scene. There’s something irreplaceable about nature. Not just greenery—office plants had a small positive effect, but one that paled in comparison to a natural view. Just adding a few natural elements to a windowful of buildings or parking lots raised employee satisfaction by a significant amount. Workers with nature views reported feeling less frustrated, more patient, and more satisfied with their jobs. Perhaps improbably, they also felt their jobs were more challenging and expressed greater enthusiasm for their work, despite the fact everyone surveyed had relatively similar jobs. Furthermore, workers with nature views also reported fewer ailments than those without.

People with outdoor jobs in natural settings—park rangers and park maintenance staff—had it best of all. They said their jobs were less demanding, lower pressure, less frustrating, and so on. It’s possible that such jobs are actually less demanding and lower pressure, but given how nature affects office workers, I wouldn’t be surprised if being immersed in nature plays an important role.

Alas, as a writer I don’t have many excuses to work outside. But I shouldn’t complain too much. My three trees are certainly better than Peter’s view before his renovations and far better than many people who work in windowless caverns.

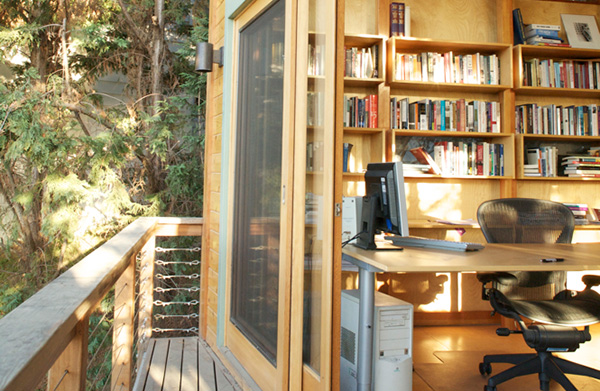

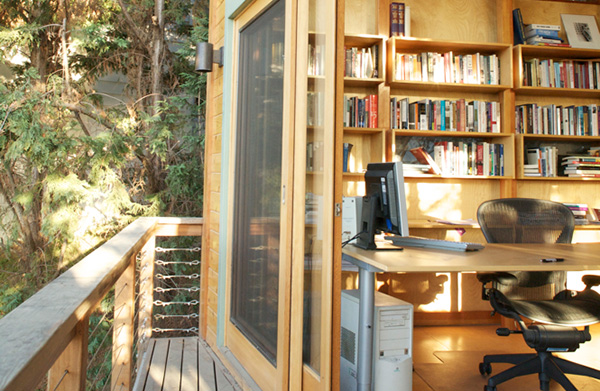

Photo by Jeremy Levine Design.

Source:

Kaplan, R. (1993). The role of nature in the context of the workplace Landscape and Urban Planning, 26 (1-4), 193-201 DOI: 10.1016/0169-2046(93)90016-7

Related posts:

It’s not the yard that matters, it’s the view

Managing landscapes for aesthetics

Thinking about how we think about landscapes