NASA’s latest image of the entire Earth may not be the most detailed to date, but it captures the imagination in ways some earlier versions didn’t. Not only does it look more natural and less computer-generated, it also recalls the first Blue Marble image—one that changed the way people thought about the Earth. The image’s natural feel and nostalgic overtones are important both for NASA’s future and our own relationship with the planet. Continue reading

For metros, two cities can be better than one

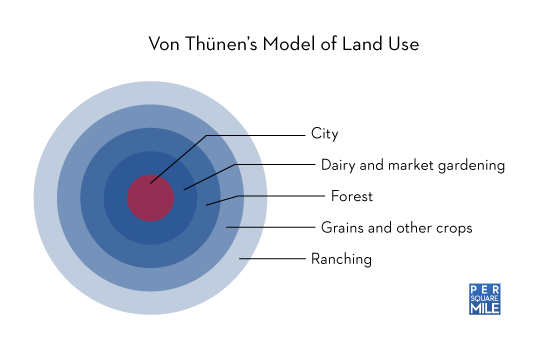

Cities were, for thousands of years, distinct and easily identifiable entities. You were either in the city or in the country. Medieval cities took this to the extreme, building walls to make explicit the distinction. Johann Heinrich von Thünen systematized the idea in 1826 when he sketched a hypothetical map that, when simplified, looked like a bow-and-arrow target. The city sat in the center and was surrounded by rings of successively less valuable farmland. It was all very orderly and very German. And for a while it did a good job describing the relationship between the city and the hinterland.

Then came the railroads and automobiles that shot holes through von Thünen’s well-organized bullseye. And in places where two cities were less than a few dozen miles apart, even the boundary between the two became blurred. Today, it’s not uncommon to find metropolitan areas with two, three, even four major cities anchoring them.

Multi-city metros would seem to be a many-headed monster, riddled with contrary opinions and paralyzed by indecision. But that doesn’t alway seem to be the case. As far as labor productivity is concerned, multi-city metros—or polycentric metros, as the literature calls them—may have a distinct advantage. A study of all metropolitan areas in the United States with populations above 250,000 by Evert Meijers and Martijn Burger shows that productivity is higher in metros with more than one city. The effect is especially pronounced among smaller metro areas.

Meijers and Burger speculate that’s because smaller cities tend to have smaller problems—less traffic, lower crime rates, and so on. By splitting the problems up among a few cities, polycentric metros can host a large population without experiencing the problems of a similarly sized, monocentric metro.

But the advantages of multi-city metros diminish as the entire area’s population grows. It’s as though the larger entity needs one place to focus its efforts. So a metro area with two cities, each one-half the size of London, wouldn’t necessarily be more productive than London itself.

Multi-city metros also fall short on other critical parts of city life—cultural and leisure opportunities. Cultural outposts like opera houses and art museums benefit greatly from larger populations, which typically contain more benefactors, both wealthy and otherwise. The same goes for sports teams. Every city would like one for themselves. Say Ft. Worth wants to build an art museum. It’s probably not going to attract some donors from Dallas, who would rather see one built in their city. Chicago doesn’t have such a problem. Monocentric metros don’t have to worry about sharing.

As cities’ borders swell, multi-city urban agglomerations are probably going to be more and more common. Even within existing metropolitan areas, smaller cities could rise to prominence. Minneapolis and St. Paul, for example, have had to contend with the rise of Bloomington. The key will be for leaders to learn to work together, coordinating efforts rather than stepping on each other’s toes.

Sources:

Meijers, E. (2008). Summing Small Cities Does Not Make a Large City: Polycentric Urban Regions and the Provision of Cultural, Leisure and Sports Amenities Urban Studies, 45 (11), 2323-2342 DOI: 10.1177/0042098008095870

Meijers, E., & Burger, M. (2010). Spatial structure and productivity in US metropolitan areas Environment and Planning A, 42 (6), 1383-1402 DOI: 10.1068/a42151

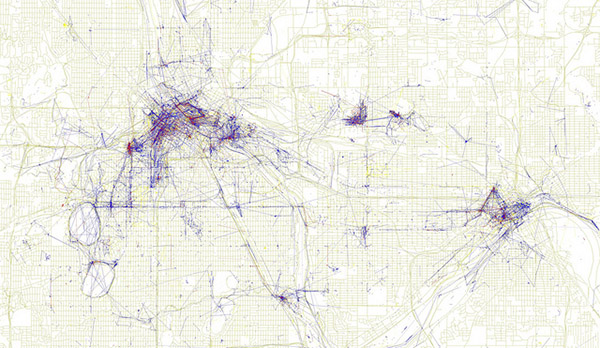

Map of the Twin Cities by the inimitable Eric Fischer.

Related posts:

Glacier thief arrested in Chile ∞

Rory Carroll:

Climate change sceptics have acquired a new explanation for why glaciers are retreating: it’s not global warming, it’s theft.

History of the cruise ship ∞

Adam Curtis explores the history of floating cities on the sea—also known as cruise ships—from their inventor’s utopian ideals to the exploitative practices that define the industry today:

In many cruise ships there are hundreds of workers from some of the poorest countries on earth who are paid minute amounts of actual wages – sometimes less than two dollars a day – to attend to the passengers’ needs.

Many of the ships’ workers can only get a living wage on the whim of the thousands of passengers above them – on the tips they choose to give them. And in the strange fun-world of the superliners the waiters, the cabin staff, the cooks and everyone else who serves, live in a state of continual vulnerability – unprotected by most of the employment laws that apply on land. Meanwhile many of the companies that own the vast ships pay practically no tax at all.

But it wasn’t always supposed to be like that.

Via Adam Rogers.

North American travel patterns, revealed by Twitter ∞

Eric Fisher is at it again. His maps are black and white and simply beautiful.

Don’t miss his map of European travel patterns, either.

China's largest freshwater lake disappears ∞

Not good, though not as depressing as the story of the Aral Sea.

Allure of the Chinatown bus ∞

Eric Jaffe, writing at The Atlantic Cities:

In research published in the latest issue of Urban Geography, Rutgers doctoral students Nicholas J. Klein and Andrew Zitcer examine the source of this enthusiasm among regular Chinatown bus riders. After conducting five focus groups with riders, Klein and Zitcer discovered that Chinatown curbside devotees see the service not just as a means of transportation but as an “authentic urban experience, a thrilling and danger-enhanced departure from daily life, and as an engagement with the multicultural city.”

Thrilling, that is, if you make it to your destination.

Honeybee highways ∞

Louise Tickle, writing for The Guardian about habitat corridors writ small:

With more than 90% of the country’s flowering meadows gone because of intensive agriculture, what’s left is just fragments of land offering the occasional oasis of nectar. Getting bees, and the pollen they carry, from one fragment to the next – which may be hundreds of metres away – is a problem. And this is where hedgerows come in.

It’s well known that hedgerows are used as corridors by birds and mammals. What Ollerton, his colleague Dr Duncan McCollin, and their PhD student Louise Cranmer discovered by close observation of their subjects’ flying patterns was that the nearer bees and butterflies got to hedgerows, the straighter they flew alongside them.

Mapping scientific collaboration ∞

Similar to the Facebook friendship map, but representing something that might be more consequential in the grand scheme of things.

Via David Dobbs.

What's a good chicken per cage ratio? ∞

The proper answer is probably zero, but NPR’s Dan Charles reports on the baby steps egg farmers are taking to give egg-laying chickens more room, along with the odd partnership they’ve formed with the humane society to enact a federal law and the even odder enmity with cattle- and dairymen.

So if United Egg Producers, representing 95 percent of all U.S. egg production, wants this law and some of the industry’s fiercest enemies do too, who could be against it?

Well, as it happens, some influential farm organizations. Beef producers, hog farmers, dairy farmers and the American Farm Bureau have all lined up against it.

Bill Donald, a rancher in Melville, Mont., and president of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, says it would be a terrible precedent to get the government involved in keeping farm animals happy. Who knows what regulations might come next?

I’m sure if egg farmers—and egg eaters—can swallow an incremental increase in price, then pig, cattle, and dairy farmers could handle it, too. A few pennies a pound would be well worth it to give these animals a bit more room.

Literate cities not always the wealthiest ∞

Jack Miller, author of Central Connecticut State University’s annual report on literacy in American cities:

These findings suggest that a city’s quality of literacy has to do with many decisions that go beyond just how wealthy and highly educated is the population. Even poorer cities can invest in their libraries. Low income people can use the Internet. Low income cities can produce newspapers and magazines that are widely read throughout the region.

That’s good to hear. Libraries may seem like a nagging line-item in a city budget, but they’re worth more than many people think.

Via The Atlantic Cities.

Pack 'em in ∞

Ariel Schwartz at Fast Co.Exist:

A prototype of Hiriko, which was developed in collaboration with seven automotive suppliers in Spain, is so compact that passengers can only get out by pushing the glass shell open. It’s a good thing the car doesn’t require gas; there isn’t even room for a gas tank. But when folded, three Hiriko vehicles can fit into a single parking space.

If you have a 55 square foot (or 5 square meter) space you’re dying to cram a car into, you’ll have to wait. The consortium plans on first selling them to city governments for car sharing programs.

Rise of the megacity ∞

Paul Webster and Jason Burke writing for The Guardian:

Experts estimate that the number of megacities of more than 10 million inhabitants will double over the next 10 to 20 years.

They just keep getting bigger.

Why New York City keeps getting bigger

Q: Why is New York City the most populous city in the United States?

A. Because it was America’s most populous city in 1900.

Q. Why was New York City America’s most populous city in 1900?

A. Because it was America’s most populous city in 1800.

History seems to be protecting New York City’s status as the most populous city in the United States. Indeed, Paul Krugman has suggested that accidents of history gave New York City a leg up on others, and that once favored it grew into the metropolis we know today. But New York is not alone. Since 1840, the densest American cities have not only grown substantially, they also represent a larger share of the American population. The same can be said of other world cities, too. They are like snowballs—they’re big and they keep on getting bigger.

But how big cities gained the upper hand is not necessarily an accident, as Krugman’s use of the word might suggest. What has helped them grow so large is actually a specific set of geographic characteristics—location near an ocean or river (or better, both), mild climate, and ready access to natural resources. City founders may not have been working off a checklist, but they knew where to site their settlements to make the most of their surroundings.

It’s no surprise that prosperous cities are often located near large bodies of water. Water is the cheapest way to move goods, and was even more so before the Industrial Revolution. Access to navigable water meant food and raw materials could be easily brought to market and goods manufactured in the city could be cheaply exported. Water facilitated the movement of ideas, too. Both New York City and San Francisco, for example, benefitted from their status as major gateways for immigration. Immigrants were not merely a source of labor—they brought with them a diversity of ideas. Eventually, the importance of water subsided as railroads and interstate highways were built. Yet cities that were founded on coastlines or rivers continued to dominate.

Their size was the secret to their success. One of Krugman’s important early contributions was a model that showed how an already large city could grow to dominate the region. His theory was really nothing new—Johann Heinrich von Thünen described nearly the same thing in 1826—but Krugman translated the concept into today’s mathematical vernacular. Other researchers quickly picked up the thread and dug out real-world evidence of the snowball effect, including one study that looked at population growth in nearly 800 American counties between 1840–1990. It found that not only did the biggest cities grow during that time, they grew at a faster rate than other cities. New York grew more than the rest because it was bigger than the rest.

Today, New York’s fate doesn’t depend on the ocean or the river, but it does owe its status to their confluence. Its geographic past continues to steer its future. I’m tempted to haul out a favorite phrase of mine—ghosts of geography—but these cities aren’t really ghosts. They’re are very much alive. Oceans and rivers may not be as relevant to today’s world cities as they once were, but without them, many cities wouldn’t be as successful. From that perspective, it seems less likely that the founders of New York, London, and Tokyo stumbled on a happy accident and more likely that they had a keen understanding of geography.

Sources:

Ayuda, M., Collantes, F., & Pinilla, V. (2009). From locational fundamentals to increasing returns: the spatial concentration of population in Spain, 1787–2000 Journal of Geographical Systems, 12 (1), 25-50 DOI: 10.1007/s10109-009-0092-x

Beeson, P. (2001). Population growth in U.S. counties, 1840–1990 Regional Science and Urban Economics, 31 (6), 669-699 DOI: 10.1016/S0166-0462(01)00065-5

Gibson, Campbell. 1998. Population of the 100 largest cities and other urban places in the United States: 1790 to 1990. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Population Division Working Paper No. 27.

Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing Returns and Economic Geography Journal of Political Economy, 99 (3) DOI: 10.1086/261763

Photo by Greg Knapp.

Related posts:

Perils of roadbuilding in the tropics ∞

William Laurance writing at Yale Environment360:

Although the direct effects of roads are serious, they pale in comparison to the indirect impacts. In tropical frontier regions, new roads often open up a Pandora’s box of unplanned environmental maladies, including illegal land colonization, fires, hunting, gold mining, and forest clearing. “The best thing you could do for the Amazon,” said the respected Brazilian scientist Eneas Salati, “is to bomb all the roads.”

Big projects like the Belo Monte dam receive the lion’s share of attention, but the profusion of roads in the Amazon poses a greater threat. That’s not to say Belo Monte is net-positive for the environment—it’s probably not—but while we’re gasping in horror at the big gash, the Amazon is busy bleeding to death from a thousand smaller cuts.

Does the leap second matter? ∞

Scott Huler has a great take on the leap second debate:

If you decide to leave the leap seconds out, the atomic clocks and the universe itself begin sailing on different paths. In a year or two your atomic wall clock and your radio station will disagree, and in a few thousand years they’ll be completely catywampus. It sounds like nothing, but in a world where we’re constantly encouraged to interact through screens and speakers, where we exist in climate controlled environments whose very existence is systematically dismantling the actual climate, anything that reminds us there’s a real world out there is a positive…

Divorcing superaccurate timekeeping from the universe it’s meant to describe solves no problem and exacerbates a profound one. Don’t do it.

Huler and I spoke about this at ScienceOnline 2012, and I think he’s right. Here on Earth, time plays a very specific role—to help us know where the Earth is in both its rotation and orbit. It also has very important cultural meanings—think high noon, midnight, and so on. It just so happens that it’s also useful in synchronizing things like computers, phones, satellites, and telescopes.

But there’s also another argument against abandoning the leap second, one to which Huler alludes in the first paragraph I quoted: The leap second debate is really an argument over scale. Certain people don’t want to deal with the issue in the near term and would rather push it off to some unspecified point in the future. It’s human nature to procrastinate—homework, chores, climate change—but inaction doesn’t solve the problem. Eventually, we’ll have to add a leap minute or a leap hour. When that happens, I’m guessing our descendants will wish we had just stuck with the leap second.

Tell me what you see ∞

John Pavlus unearths a stunning set of maps over at Fast Co. Design:

Traditional city maps visualize just one aspect of urban design–the city’s intended structure, full stop. But add in a layer that visualizes how people actually use the city, and then the map becomes much more interesting. Eric Fischer did exactly that when he used Twitter’s API to collect tens of thousands of geotagged tweets and map them onto the streets of New York, Chicago, and the San Francisco Bay area.

What results are a series of inkblot webs that could easily be mistaken for blood vessels or root systems if the silhouettes of the cities they represent weren’t so charismatically obvious. Pavlus has a great eye for infographics, and these are no exception.

Unhealthy commutes or unfinished analysis? ∞

This piece by Anne Price and Ariel Goodwin seems compelling at first glance, but I’ve grown more skeptical the more I read over. In it, they show a purported link between mode of commute (driving or carpooling vs. walking or biking) and obesity rate. The maps and figures they post are convincing enough, but here’s where I begin to take issue with their analysis:

As the Oct. 2011 article pointed out, the relationship between sedentary travel and health outcomes can be misleading when additional contributing factors are not taken into account. While it is not our intent to claim a direct causal link between transportation modes and obesity rates, it is hard to deny the existence of some geographic patterns.

And yet that seems to be exactly what they are doing. Here’s my question: Why didn’t they include those variables? That would have more clearly placed the role of commute mode in context.

The United States of Open Space ∞

Neat maps by Steven Von Worley on where people don’t live in the United States.

Feeding more with less ∞

John Vidal considers the future of food at The Guardian:

By 2050 there will be another 2.5 billion people on the planet. How to feed them? Science’s answer: a diet of algae, insects and meat grown in a lab.

Those three are staples of nearly every sci-fi diet—which would normally make me think twice about reading the rest of the article—but Vidal also looks beyond the clichés, profiling advanced selective breeding and desert farming with with salt water.