Never buy a car with a salvage title. Anyone who has ever driven a car after a major accident can tell you why—it’s just not the same as before the crash. Though all the parts might be in the right place and the paint just as shiny as before, there’s invariably some new rattle, shake, or whistle that you can’t fix. The magic that is gone, and nothing will bring it back. Cars are a lot like primary tropical forests in that way.

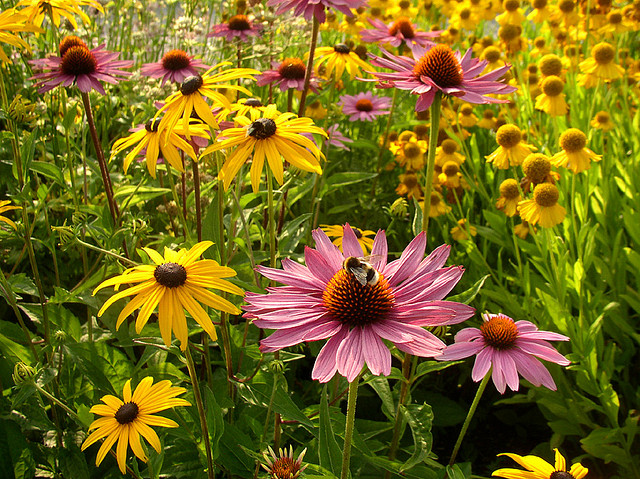

Biodiversity thrives in undisturbed tropical forests. But once they have been selectively logged, burned, or leveled, what grows back in their place just isn’t as rich, vibrant, or diverse as the original, according to a new paper released online today in Nature. The meta-analysis—written by a number of authors including Bill Laurence and Tom Lovejoy, two deans of tropical conservation—synthesized 2,220 pairwise comparisons of primary and disturbed tropical forests from 138 different studies on four different continents to arrive at that one conclusion.

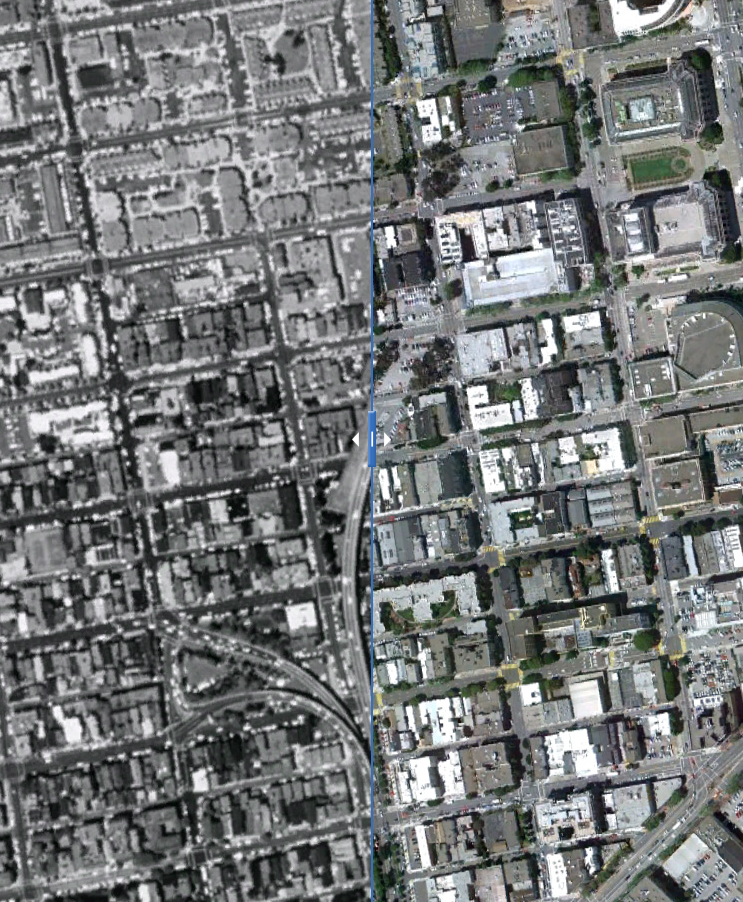

The dominant image of deforestation—at least from an American perspective—is the Amazon. Photographs and satellite images of logging and agricultural conversion show in graphic detail splintered tree stumps, smoking ashes, and herringbone tentacles of human influence. But while the authors found South American forests are greatly threatened by human disturbance, Asian forests are even more imperiled.

To compare results from numerous studies, the study’s authors the measured effect size of human disturbance on biodiversity. It’s a statistical technique which describes the magnitude of differences between populations. The effect size of land-use changes in Asia was more than twice that of second place South America and even larger still than those of Africa and Central America.

To give you an idea of the severity of Asia’s biodiversity threats, let’s review the guidelines on interpreting effect sizes. Generally, a small effect size is 0.2, medium is 0.5, and large is 0.8 and above. In the study, Central America checks in at 0.11, Africa at 0.34, and South America at 0.44. (A quick caveat before we continue: The African result may not be representative. The continent’s tropical forests are understudied because of continued conflict, and future disturbance rates could accelerate in the face of population growth.) Asia is far ahead of the rest of the pack, blowing them all away with an effect size of 0.95.

Asian tropical forests are more threatened by every type of human impact than tropical forests on other continents. Agricultural conversion is responsible for a large portion of biodiversity loss in the region, with plantations and selective logging operations following not far behind. Plantations are of particular concern because the crops they yield—primarily palm oil and exotic woods—are lucrative. Their profit potential draws interest not only from multinational corporations, but governments as well. These organizations have large amounts of capital and can convert vast tracts of primary forest into ecologically sterile plantations that practically print money.

Plantations also have the advantage—for governments and corporations, at least—of looking deceptively like natural forests to many people. Asia Pulp & Paper, a company with large plantation holdings throughout Southeast Asia, has been exploiting this confusion through a series of recent TV ads. The Indonesian government has been in on the ruse, too, suggesting that it may push for their plantations—many of which were carved from primary forests—to count as forest land under REDD schemes, or reduction of emissions through deforestation and forest degradation. That means the government would not only profit from the plantations’ crops, but also from international payments to purportedly offset or reduce carbon emissions.

If we have to use forest land at all, the best bet to preserve biodiversity seems to be selective logging. Though the practice still harms overall biodiversity, it does so less than other land uses. Still, the paper’s authors caution that selective logging’s ill effects may be masked by proximity to less disturbed primary forests, which may export species to depauperate tracts. If this is the case, then selectively logged areas may be running the ecological equivalent of a trade deficit with primary forests. Without some reciprocation, the two will eventually go bankrupt.

This new meta-analysis confirms what many ecologists have long suspected—that minimally disturbed primary forests are some of the best bastions of biodiversity. It puts another hole in the idea that agroforestry projects, plantations, and even selective logging can extract resources without adversely affecting ecosystems. Like a car that’s been in an accident, primary can never be the same as before. But unlike cars, we can’t go out and buy new ones.

Source:

Gibson, L., Lee, T., Koh, L., Brook, B., Gardner, T., Barlow, J., Peres, C., Bradshaw, C., Laurance, W., Lovejoy, T., & Sodhi, N. (2011). Primary forests are irreplaceable for sustaining tropical biodiversity Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature10425

Photo by WWF Deutschland.

Related posts:

Spare or share? Farm practices and the future of biodiversity

Coaxing more food from less land

Can we feed the world and save its forests?