Samuel Arbesman plotted host cities’ populations and discovered an oddly cyclical pattern. And if you squint just right, you’ll see that cycle is trending upward. It’s global population growth, as seen through Olympic host cities.

The Perfect Host for the 2024 Games ∞

Sara Germano, writing for the Wall Street Journal:

With revenue-sharing quibbles between the USOC and the IOC resolved earlier in May, America’s next summer Olympics could come as soon as 2024, and the Journal has done some scouting for the next perfect host. It’s a sports-crazed town that hasn’t welcomed a Games before, and, what’s more, it has some of the highest Olympics TV ratings in the country. The Games of the XXXIII Olympiad should be held in…Milwaukee.

The article is more than a bit tongue-in-cheek (it’s OK—we Wisconsinites are used to being mocked by spectators on the coasts), but wouldn’t it be something? I’m sure Milwaukee would put on a hell of games.

A Few Urban Syndromes ∞

Stockholm is, of course, the most famous example. But Alexander Trevi wonders if there are others lurking out there, either inspired or inflicted by various cities.

If the world’s population lived like…

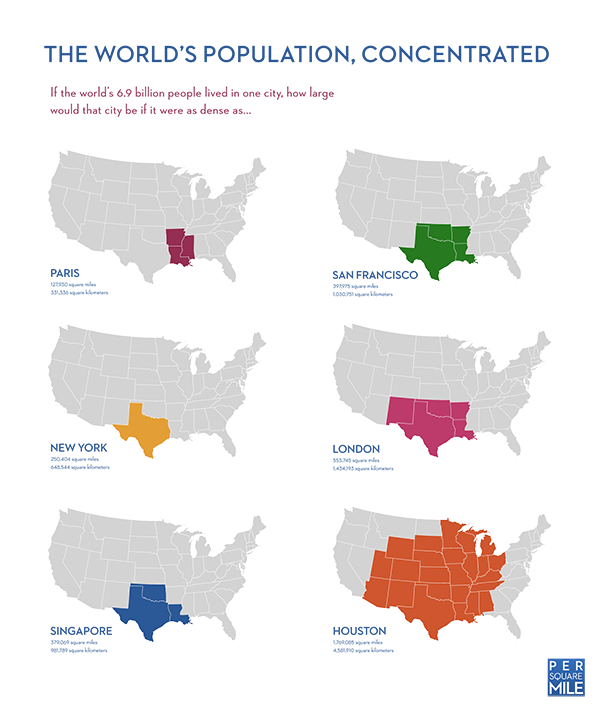

Shortly after I started Per Square Mile, I produced an infographic that showed how big a city would have to be to house the world’s 7 billion people. There was a wrinkle, though—the city’s limits changed drastically depending on which real city it was modeled after. If we all lived like New Yorkers, for example, 7 billion people could fit into Texas. If we lived like Houstonians, though, we’d occupy much of the conterminous United States.

Here’s that infographic one more time, in case you haven’t seen it:

What’s missing from it is the land that it takes to support such a city. In articles and comments about my infographic, some people overlooked that aspect—either mistakenly or intentionally. They shouldn’t have. Cities’ land requirements far outstrip their immediate physical footprints. They include everything from farmland to transportation networks to forests and open space that recharge fresh water sources like rivers and aquifers. And more. Just looking at a city’s geographic extents ignores its more important ecological footprint. How much land would we really need if everyone lived like New Yorkers versus Houstonians?

It turns out that question is maddeningly difficult to answer. While some cities track resource use, most don’t. Of those that do, methodologies vary city to city, making comparisons nearly impossible. Plus, cities in most developed nations still use a shocking amount of resources, regardless of whether they are as dense as New York or as sprawling as Houston. Any comparison of the cities in my original infographic would be an exercise in futility at this point.

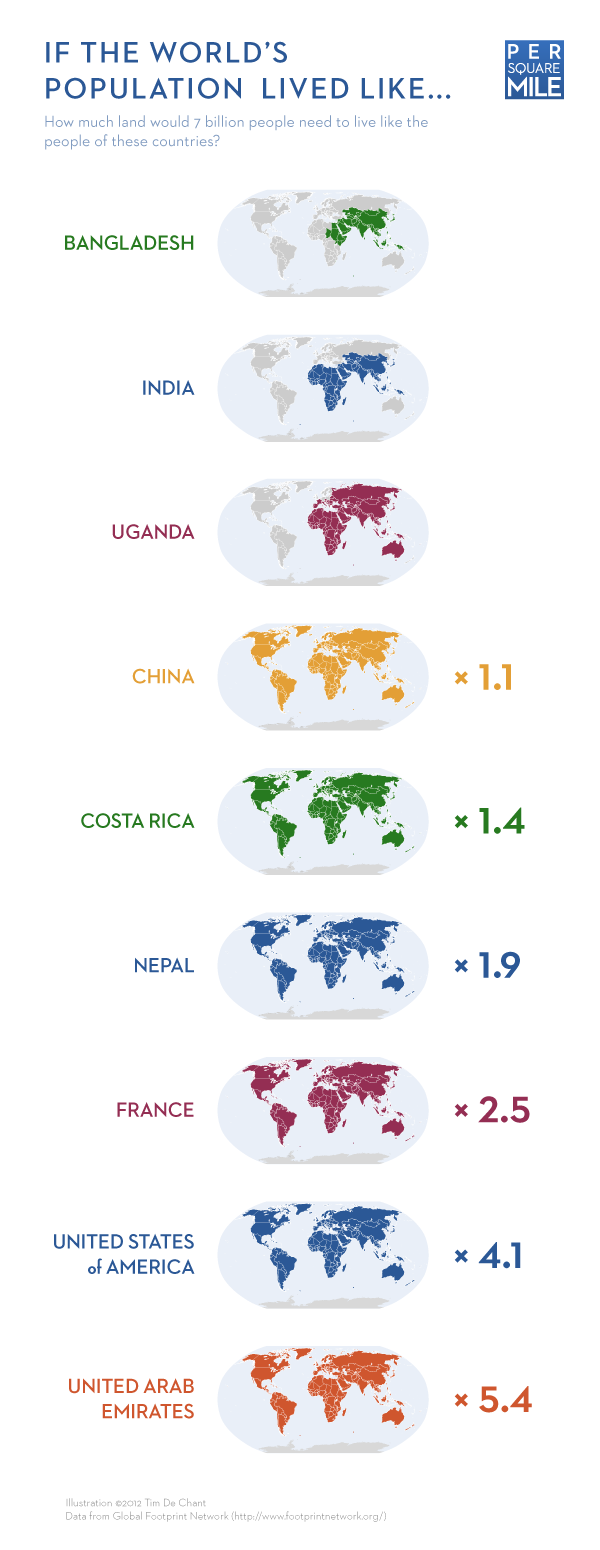

But what we can do is compare different countries and how many resources their people—and their lifestyles—use. For countries, the differences are far, far greater than for cities. Plus, there’s a data set that allows for reliable comparisons—the National Footprint Account from the Global Footprint Network. Their methodology is based on peer-reviewed research by Mathias Wackernagel, the organization’s founder. It’s consistent and comprehensive. Each country’s footprint is assembled from sub-footprints, ranging from cropland to carbon to urbanization to fishing grounds. For my purposes, I used only terrestrial sub-footprints. I’ll let the results speak for themselves.

Sources:

Global Footprint Network. 2011. National Footprint Accounts, 2011 Edition.

Wackernagel, M., Kitzes, J., Moran, D., Goldfinger, S. & Thomas, M. (2006). The Ecological Footprint of cities and regions: comparing resource availability with resource demand, Environment and Urbanization, 18 (1) 112. DOI: 10.1177/0956247806063978

Related posts:

If the world’s population lived in one city…

Spare or share? Farm practices and the future of biodiversity

Readers like you

I’d like to make a confession: I’m not a risk taker.

When I started Per Square Mile in January 2011, I figured I could carve out a small space for myself on the Internet. The stakes were pretty low—I wrote a few pieces beforehand and spent some time crafting a crisp design for the site, but that was about it.

Fast-forward more than a year and a half and Per Square Mile has developed a bit of a following—on a scale which I never could have imagined. The social media driven landscape has certainly helped. Without Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and the like, I don’t think I’d have the readership I do now. Which is really to say, without you, my readers, generously sharing my work with your friends, colleagues, and acquaintances, I’d still be talking to myself in a corner. Instead, I have tens of thousands of readers. And for that I have you to thank.

I spend many hours on Per Square Mile, from writing to design and everything in between. It has been rewarding to see so many people appreciate that hard work. I love what I do here, and I think you do, too.

That’s why today I’m announcing memberships for Per Square Mile, a way for you, my readers, to support this site. To be clear: The entire site will remain free of charge. There will be no paywall, no members’ area with separate content. But if you love Per Square Mile and want to support independent writing, this is your chance. Your kindness won’t go unnoticed.

The details

The benefits of membership include:

- Access to a members only Twitter feed that includes links to original articles and infographics as well as direct links to articles I post on the Linked List. (The existing Twitter account @PerSquareMile, which is articles only, will remain open to all.)

- Access to The Daily Per Square Mile, a members only email list that sends everything on the site right to your inbox every morning.

- A warm, fuzzy feeling for supporting a site you enjoy.

There are two ways to become a Per Square Mile member. One is to buy a t-shirt, the other is to contribute $19 or more. Both will give you access to members’ perks for one year.

The t-shirt and member extras are my little way of saying “thank you”. But just like no one donates to PBS to receive a tote bag, you’re probably not donating to Per Square Mile just for the t-shirt or the Twitter feed.

Still, the t-shirts are top-notch. They’re printed on American Apparel’s 100% cotton t-shirts and come in both men’s and women’s styles. The printing process is special, too. I chose to use discharge and water-based inks rather than what’s used in the standard silk screening process, which means the print is actually integrated into the cotton fibers. No plasticky feel, no cracking, no peeling. Just the shirt’s soft fabric. It’s more stylish, more comfortable, and more durable.

I’ll be selling Per Square Mile t-shirts only a couple of times a year for only a few weeks at a time, so strike while the iron is hot. There will be one large print run to make things manageable. Shirts will ship out in the middle of September, but your member benefits will be available immediately.

A humble appeal

I’ve been hammering away on this site for over a year and a half now, and I’ve been trying my level best to make those efforts worth reading. I’d like to think I’m succeeding, in part because the site is one of a kind. Really. I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say there’s nothing quite like Per Square Mile out there.

As I said earlier, I’m not one to take risks. Yet here I am, dipping my toe into uncharted waters. It may not seem risky on the surface, but believe me, it feels that way. I’m asking you what you think of Per Square Mile, and by extension, what you think of me as an author. I’m asking for your support.

Slovenia Leads Games in Medals Per Capita ∞

Ken Belson, writing for the New York Times:

What is perhaps more compelling are the nations that carry their weight in medals, like Slovenia. The Slovenes have won four medals: gold in judo, silver in track and field and bronze in rowing and shooting. With a population of 2.06 million people, that works out to one medal per 514,385 residents, the best per-capita medal rate among the 59 countries that have won at least one medal through Sunday.

I was actually thinking last night, why haven’t I heard much about India in the Olympics? Turns out they have won a few medals, but they have the lowest number per capita of any country that’s been on the podium.

Tucson's disappearing greenspace ∞

Tucson’s population has more than doubled since the 1960s. The city’s footprint has also swelled, now sprawling far into the surrounding desert. But the Tucson area has lost more than saguaro habitat—the city has slowly nibbled away at the riparian zones along the Santa Cruz River (running along the west side of the photos) and Rillito River (running along the north side). Take a look.

August 22, 1965, taken by Gemini V astronauts Gordon Cooper and Pete Conrad.

October 28, 2011, taken by Landsat 5.

The loss of that habitat is significant—riparian zones are often much more productive than their surroundings, especially so in deserts. The question that’s bugging me is, why did Tucson gobble up that important habitat and not the surrounding desert (of which there is plenty)?

How Urban Parks Enhance Your Brain, Part 2 ∞

Eric Jaffe has uncovered another study on the benefits of parks. This one addresses a detail lacking in the others: Is there an optimal number of trees?

The most intriguing conclusion to be drawn here is that the size of an urban park isn’t nearly as important as the density of its vegetation.

The less of the city we can see, the better, apparently. That fits with the results of another study I wrote about a while ago. It found that, when it comes to a sense of privacy, it’s not the size of people’s yards that matters, it’s the view.

One problem, though—while thick vegetation may have a psychologically restorative effect, it can also encourage crime. Planting trees and shrubs willy nilly seems like a simple solution to block cities’ ill effects, but clearly urban landscaping needs to be more thought out than that.

The long tail of names in cities ∞

Robinson Meyer, writing for The Atlantic:

What both these maps reveal are the cities’ long tails of names and origins, and of how, when you get down to it, something totally banal — zoning and electoral data — describes the flow of bodies, families and migrations.

What if the U.S. was more like Europe, geopolitically? ∞

Regular PSM readers know I love maps that envision an alternate reality, one that’s both very different and very familiar. To wit.

Well, Frank Jacobs found another set, these by “Leopold Kohr, a 20th-century Austrian academic whose work inspired both modern political anarchism and the Green movement.” The gist of the maps? What if political divisions in the U.S. were more like Europe, and Europe were more like the U.S.

Why Americans and Europeans Give Directions Differently ∞

Erik Jaffe, writing for the Atlantic Cities:

It stands to reason that these different environments would leave distinct impressions on their respective residents. If the place you live in looks like a map, logic suggests you’ll start to discuss it like one. Likewise, if the place you live in has a unique layout, you’ll need more precise identifiers to describe it.

Canada's Cahokia ∞

Owen Jarus, writing for Live Science:

Scientists estimate between 1,500 and 1,800 individuals inhabited the site, whose fields encompassed a Manhattan-size area. To clothe themselves they would have needed 7,000 deer hides annually, something that would have required hunting about 26 miles (40 km) in every direction from the site, Williamson said.

Not as big as the real Cahokia, but impressive nonetheless.

American Accent Undergoing Great Vowel Shift ∞

Given our media-obsessed culture, you would think that regional accents would homogenize. But as this older radio piece by Robert Siegel shows, the exact opposite is happening.

Drought and food prices ∞

Annie Lowrey and Ron Nixon, reporting for the New York Times:

“It is one extra kick in the stomach” for low-income families, said Chris G. Christopher, senior principal economist at IHS, a consulting firm. “There’s a lot of people in this country living paycheck to paycheck. This is not a good thing for them.”

Extreme weather and engineering assumptions ∞

Matthew L. Wald and John Schwartz, reporting for the New York Times:

Excessive warmth and dryness are threatening other parts of the grid as well. In the Chicago area, a twin-unit nuclear plant had to get special permission to keep operating this month because the pond it uses for cooling water rose to 102 degrees; its license to operate allows it to go only to 100. According to the Midwest Independent System Operator, the grid operator for the region, a different power plant had had to shut because the body of water from which it draws its cooling water had dropped so low that the intake pipe became high and dry; another had to cut back generation because cooling water was too warm.

So much of our infrastructure assumes certain climatic conditions, many of which are being thrown out the window. And it’s not just high-tech installations like nuclear power plants. Just last summer, I was pulling out of a Target parking lot when it sounded like I had a flat. It wasn’t. It was tar that the summer heat had baked beyond its limits. Instead of remaining stuck to the pavement, it stuck itself to my tire.

Bottom line? Climate change will to force us to redesign almost everything, from road tar to nuclear power plants.

To compete, organic farming must find its place

Fans of organic farming: There’s something I have to tell you. Conventional farming isn’t going anywhere. Fertilizers, herbicides, insecticides, the works. They’re here to stay. But I also have something else to tell you. In certain places, organic farming could supersede conventional practices. The trick is, we have to find out where those places are.

Plenty of ink has been spilled over the nitty-gritty of organic farming—what type of natural fertilizers work best, which species of insects farmers should court to ward off pests, and so on. But little has been done on a larger scale, like which regions might be better suited to organic practices. Little, but fortunately not none.

I’ve found two papers that I think, when considered together, show where organic farming can make its biggest impact. The first comes from Germany, where Teja Tscharntke and colleagues reviewed scads of scientific papers on organic farming. They noticed that fields surrounded by healthy portions of wilderness can be farmed either organically or conventionally without significantly harming the ecosystem.

Put differently, that means organic farming won’t do much to boost species diversity and abundance in complex, species rich landscapes—the benefits are less substantial where the landscape is less degraded. That’s a pretty obvious statement, but it’s corollary is more interesting: Organic farming might be more beneficial in simple landscapes dominated by intensive farming.

Like in Asia. Farming in Asia is more extensive than in Europe. Where European farms are often interrupted by woodlots, Asian farms tend to form an uninterrupted carpet. Raw statistics bear this out. According to the World Bank, farmland in the European Union occupies about 45 percent of the land (or less than 30 percent if you include the eastern part of the continent), while in East Asia that number is closer to 50 percent. And where forests do exist in East Asia, they’re being lost more rapidly than anywhere else in the world.

Organic farming could benefit East Asian countries more, according to a paper by Tatsuya Amano and colleagues in Japan.¹ They focused on rice paddies across Japan’s 3,000 kilometer north-south span, sampling the abundance of a particular group of spiders, Tetragnatha species, a widely distributed genus found in forests, grasslands, and rice paddies. When the researchers studied the distribution of spiders in the country’s organic farms, they found that organic methods boosted spider numbers most in wetter and warmer regions.

They cite two reasons for this. First, there’s strong evidence that spiders thrive in wetter areas. Second, warmer, wetter regions tend to have what ecologists call “high energy” ecosystems. Rainforests are a good example; there’s so much sunlight, warmth, and water that life can barely contain itself.

When you consider these two papers together, you can see where organic farming would be most beneficial—warmer, wetter regions with extensive farmland. In other words, tropical Asia, Africa, and South America. Unfortunately, those places are, with the exception of Japan, among the least likely to have organic farms. Part of this is economics—conventional farming still produces food more cheaply, and people in developing countries don’t have the money to pay a premium for organic. Another is education. In the drive to raise food production, organic farming isn’t always considered. In part that’s because conventional agriculture is a known quantity. Developed nations ramped up farm productivity with those techniques. Why wouldn’t developing nations go with a sure thing?

But if this new research is anything to go by, the script should be tweaked for developing nations. Organic farming certainly pays dividends environmentally, but it could boost farm output in tropical and sub-tropical regions, or at least farm profitability. Even when forgoing costly inputs like pesticides, farmers can still control pests by accommodating beneficial bugs, which in turn gain the most from organic methods in wet, warm regions.

Despite its successes, organic farming still languishes in a niche—selling to farmers’ markets and boutique grocers—within another niche—the developed world. To break out, it’ll have to identify where it can be most effective. Organic farming has trouble competing with conventional agriculture in complex, low energy landscapes like those found throughout Europe or parts of the United States. But if organic farming really does excel in simple, high energy landscapes like those in tropical Asia, then there’s potential for change on a global scale.

- Japan isn’t included in the World Bank data on East Asia, but their land use patterns aren’t substantially different. ↩

Sources:

Amano, T., Kusumoto, Y., Okamura, H., Baba, Y.G., Hamasaki, K., Tanaka, K. & Yamamoto, S. (2011). A macro-scale perspective on within-farm management: how climate and topography alter the effect of farming practices, Ecology Letters, 14 (12) 1272. DOI: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01699.x

Tscharntke, T., Klein, A.M., Kruess, A., Steffan-Dewenter, I. & Thies, C. (2005). Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity – ecosystem service management, Ecology Letters, 8 (8) 874. DOI: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00782.x

Photo by Tormod Sandtorv.

Related posts:

Spare or share? Farm practices and the future of biodiversity

Earth as art: 5 most popular Landsat satellite images ∞

Betsy Mason, writing for Wired:

The first Landsat satellite was launched on July 23, 1972. To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Landsat mission, the public was given the difficult task of choosing the best of the more than 120 images in the Earth as Art collection.

Earth + false color imagery = stunning.

Happy birthday, Landsat ∞

Landsat turns 40 this week. This image, taken on July 25, 1972, was the first it sent to the archives.

British rail ridership up 50 percent in last decade ∞

Why? Because they invested in the infrastructure.

Why Motor Trend loves high-speed rail ∞

David Levitan’s autonomous car piece reminded me of an op-ed Motor Trend ran last year supporting high-speed rail. Their reasoning? HSR would forestall autonomous automobiles—which many car enthusiasts hate with a passion—by freeing up space on jammed roads. Those who actually like to drive would get to do so instead of idling along.