TED is currently in full swing, and the program this year has an entire section devoted to the city. Fitting, given that this year’s TED Prize went to a city-centric project, one that hopes to crowdsource ideas to solve urban problems and reinvent cities. It’s predictably named The City 2.0. The site has a flashy splash page, but the innards still need some work—tapping in my current city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, sent me to a generic index page that encouraged me to “get connected” with other aspiring urban planners in my area, but responded to my clicks with little more than a broken Google Maps interface and some “COMING SOON” dialog boxes. For now, it’s long on pizzazz and short on details.

The TED Prize website fortunately has more on what The City 2.0 hopes to accomplish:

For phase I, the website (www.thecity2.org) will focus on helping individuals in forming cross-disciplinary groups to:

- determine the issue they want to tackle (i.e. traffic, lack of trees);

- determine a solution;

- develop an action plan;

- work to implement the solution;

- share the story of their success or failure with others.

Companies and organizations will be able to offer their tools to site users for use in executing their action plans. Ten micro grants of $10,000, coming out of the $100,000 TED Prize money, will be awarded in July 2012 to ten local projects that have the best hope of spurring the creation of their City 2.0.

To be clear, that’s $100,000 to be equally split among ten groups. Not a lot of money to tackle problems that probably need millions, even billions, of dollars thrown at them. Thankfully, there’s more:

As the site continues to grow and the overall platform grows we expect to:

- expand the functionality for individuals to connect and act;

- develop and design templates for knowledge sharing between new ideas formulated on the site and preexisting projects;

- build out our resource section with new local and global partners;

- introduce technology solutions for non-web based communities;

- expand our financial incentive program with larger grant offerings for active projects

- establish local and/or global gatherings on the City 2.0.

That’s a little better. This part of the project should have a longer-lasting impact than the small pot of grant money. Local civic groups often don’t have the skills or wherewithal to build a connected platform to publish their ideas and solicit feedback. The City 2.0 could provide that. But soliciting ideas is just the beginning. Many other hurdles stand in the way, and from what I can see The City 2.0 doesn’t propose how to address them.

The most obvious barrier is money. The City 2.0 acknowledges that to be successful it needs “companies and organizations willing to offer empowering resources” and “financial support”. It seems to me they are simply hoping companies and philanthropists will step forward and reward the best projects. That’s papering over a big problem.

The next issue is how to choose the best project. The City 2.0 says in its intro video that it will “combine the reach of the crowd with the power of the cloud”. Both crowdsourcing and the cloud are hot topics these days. Crowdsourcing in particular can give people a voice who otherwise may not have spoken up, and it leverages the law of big numbers to extract a handful of singular, stand-out ideas. But the real problem with crowdsourcing solutions for cities is more fundamental than that: Who decides which ideas to implement?

Lior Zoref, a crowdsourcing advocate, gave a TED talk this year about the wisdom of crowds in which he was joined on stage by an ox. After the gasps died down, he asked everyone to guess the weight of the animal and submit it to a website. At the end of his talk, he announced the average of the audience’s guesses: 1,792 pounds. The real weight of the cow? 1,795 pounds.

It is an impressive demonstration, but one that doesn’t sell me on the crowd’s ability to reinvent the city. That’s because crowd wisdom cannot apply to projects like The City 2.0. With the ox’s weight, there is one right answer. The crowd’s wisdom can be unambiguously verified. But with ideas and concepts like those solicited by The City 2.0, there is no right answer. And you certainly can’t distill an “average” idea from them all. Ultimately, a panel will have to pick the winners and losers. Those panelists will have enormous sway over the outcome of The City 2.0. If they are experts in their field, what’s to say the winners will be revolutionary, or even substantially different from their own work?

If winners are picked by popular vote—which I highly doubt—that, too, is no guarantee that the most promising proposals will be selected. People don’t always know what they want. “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups,” Steve Jobs once said. “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” There may be wisdom in crowds, but genius is usually confined to individuals.

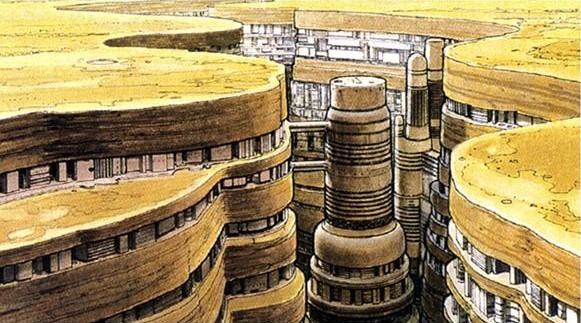

I suspect it’ll take true genius to remake the city. We’ve been spinning our wheels in recent years, rehashing concepts of the city that have been around for decades, even centuries. Those ideas may have worked well in the past, but they didn’t have to contend with airports, globalization, or climate change. Today’s best solution may be unlike anything we have come to expect from cities.

I’m sure The City 2.0 will fund some great projects, but we won’t really know how they work until we really try them. Not small bits here and there, but big implementations. Trying on that scale takes money, and the only organizations with the money to do it are governments.

Does that mean it’s back to the old way, sitting through planning meetings and zoning boards? Maybe. Crowdsourcing is a great way to gather ideas, but implementing them takes community and persistence and enthusiasm. It’s possible that a website could create that community, but I’m skeptical—most social media tools piggyback on existing, real-world social bonds. I know I sound pessimistic about The City 2.0. I’m not entirely. I hope that the project will uncover a work of genius that would have otherwise been ignored, but I’m not holding my breath.

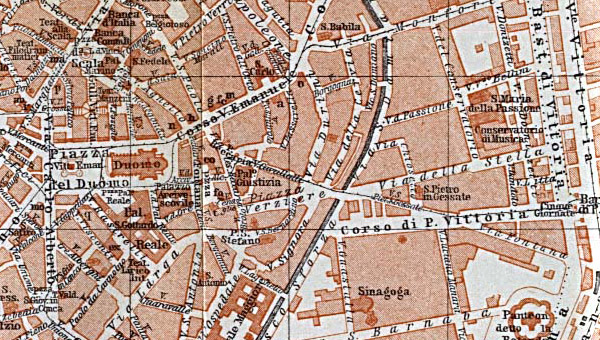

Photo from The City 2.0.