https://persquaremile.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/

A month ago, I covered a study showing how tree cover was related to income level. A couple of weeks later, I posted images gleaned from Google Earth showing how easy it is to spot income inequality from space. I also asked you, my readers, to send me more examples of the same.

The response has been overwhelming. In fact, I’m still receiving emails and comments. I haven’t been able to go through them all, so if yours isn’t below, hang tight. I’ll get to it eventually. Consider this a post that’ll be updated continuously. As they say, check back early and often.

So without further ado, here they are. This is where you see income inequality. You may see it every day, right in your own backyard. You may have stumbled across it years ago. You may have noticed on a vacation. But collectively, you see it everywhere. Keep ’em coming.

Mexico City

From Todd Gastelum, who writes:

Although it appears that these satellite images are presented at different scales, I assure you that they were not. The houses in Lomas truly are enormous whereas San Miguel Teotongo is typical of the dense, irregular urbanization characteristic of the city’s more peripheral zones.

Lomas de Chapultepec, Miguel Hidalgo

San Miguel Teotongo, Iztapalapa

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

From Aaron Krolikowski, who writes:

I’m a PhD student (in Geography) from the University of Oxford. My work takes place in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and I spend quite a bit of time looking at maps of the city. One of the first things I noticed was exactly what you mention in terms of the ability to see income inequality from a birds-eye view. I’ve shared some photos with you to give you an idea of what I look at (and live!) every day here.

The first – To the left you have unplanned settlements of “Mikoroshini” and “Makangira”…to the right, the highly affluent and very European “Oyster Bay”

The second – To the left is the informal settlement of Hanna Nassif and across the river is middle-class Upanga

Mikoroshini, Makangira, and Oyster Bay

Hanna Nassif and Upanga

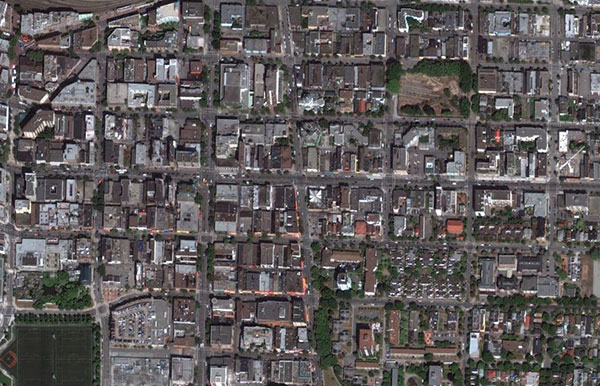

Vancouver

From Sylvian Paradis.

Downtown East Side

British Properties

Lisbon, Portugal

From João Jordão.

Cova da Moura, Amadora

Cascais